For some 3,000 years, people have turned to the I Ching, the Book of Changes, to help them uncover the meaning of their experience, to bring their actions into harmony with their underlying purpose, and above all to build a foundation of confident awareness for their choices.

Down the millennia, as the I Ching tradition has grown richer and deeper, the things we consult about may have changed a little, but the moment of consultation is much the same. These are the times when you’re turning in circles, hemmed in and frustrated by all the things you can’t see or don’t understand. You can think it over (and over, and over); you can ‘journal’ it; you can gather opinions.

But how can you have confidence in choosing a way to go, if you can’t quite be sure of seeing where you are?

Only understand where you are now, and you rediscover your power to make changes. This is the heart of I Ching divination. Once you can truly see into the present moment, all its possibilities open out before you – and you are free to create your future.

What is the I Ching?

The I Ching (or Yijing) is an oracle book: it speaks to you. You can call on its help with any question you have: issues with relationships of all kinds, ways to attain your personal goals, the outcomes of different choices for a key decision. It grounds you in present reality, encourages you to grow, and nurtures your self-knowledge. When things aren’t working, it opens up a space for you to get ‘off the ride’, out of the rut, and choose your own direction. And above all, it’s a wide-open, free-flowing channel for truth.

Hello, and thank you for visiting!

I’m Hilary – I work as an I Ching diviner and teacher, and I’m the author of I Ching: Walking your path, creating your future.

I hope you enjoy the site and find what you’re looking for here – do contact me with any comments or questions.

Clarity is my one-woman business providing I Ching courses, readings and community. (You can read more about me, and what I do, here.) It lets me spend my time doing the work I love, using my gifts to help you.

(Thank you.)

Warm wishes,

Hilary”

Blog

A reading for a decision this time: Sha asked,

"If I build another tech company, what will the experience be like?"

Yi answered with Hexagram 27, Nourishing, changing at lines 2 and 3 to 26, Great Tending:

So that gave her an interesting couple of moving lines:

‘Unbalanced nourishment.

Rejecting the standard, looking to the hill-top for nourishment.

Setting out to bring order – pitfall.’'Rejecting nourishment.

Constancy, pitfall.

For ten years, don't act.

No direction bears fruit.'

It looks as though the experience would be not much fun at all - but why...?

Bill asked about his dating prospects, and received - of all things - the sixth line of Hexagram 24, Returning...

...which is exactly no-one's favourite line. So how do you respond when Yi's answer is all doom and gloom, and really not what you hoped to hear? You explore... so we did.

Bill kindly interviewed me for his blog afterwards: here's his article.

A listener's reading for this month's podcast: Ann asked,

'How do I integrate myself as an artist with everyday life?'

And Yi answered with Hexagram 14, Great Possession, changing at lines 1 and 3 to 64, Not Yet Crossing.

(If you enjoy this, please share it!)

One of the strangest things about conversations with Yi is how immediately relatable most of its imagery is. Life is a journey; we walk our paths (Hexagram 24). We can be stressed and over-burdened to breaking point (Hexagram 28) - it's actually next-to impossible for us to talk or think about stress without using the same metaphor. We can stretch our imaginations a little to remember that, to the Yi's authors, horses are not only beautiful and fast, but the fastest things in the world and a vital military advantage. We may not know that tigers are guardians, or associated with the west, but we know about their teeth. So we can consult with this book written several millennia ago, in an unimaginably different culture, and more often than not, understand what it's saying.

Only… then there are the offerings.

Offerings in the Yijing

Even if you are reading Wilhelm/Baynes, there are plenty of them. 'One may use two small bowls for the sacrifice' in Hexagram 41; 'The neighbour in the east who slaughters an ox does not attain as much real happiness as the neighbour in the west with his small offering,' in 63.5, for instance.

And if you turn to one of the authors who sets out to reconstruct the original, Bronze Age meaning of the text - or someone like Karcher, who made these scholars' work accessible for modern divination - the offerings are everywhere. In Rutt's version, Hexagram 23 is flaying a ewe, Hexagram 31 is chopping up a human sacrifice, Hexagram 52 is 'cleaving' some unspecified victim joint by joint, there is blood gushing all over Hexagram 59, and every instance of 'truth and confidence' has turned into war captives, on their way to the sacrificial altar. The whole book starts to sound like a helpful manual for blood sacrifice.

Rutt intended his book as a scholarly translation, of course, not for use in divination. But Karcher, who certainly did write for modern diviners, translates heng ('success' in Wilhelm/Baynes) as, 'Make an offering and you will succeed.' What offering?

The idea of 'offerings' or 'sacrifice' seem to be what makes the oracle feel most remote from us, ancient and alien. We don't have feudal lords, but we do have networks of communication and helpers - we can understand their function and what fulfils that role for us. Most of us don't own cattle, but we all understand ownership, wealth and its attractions. Most of us don't make offerings… and there is no apparent modern equivalent to take their place.

So people look at 'make an offering and you will succeed' and wonder whether they literally need to start making offerings. Or read Stephen Field's translation of Hexagram 29 -

'There is a capture. Consider offering the heart in sacrifice. A trip will be rewarded.'

- and lament that they have already sacrificed their heart to this, and they've had enough!

Part of our problem here is the colloquial English meaning of 'sacrifice'. Consider…

'She sacrificed her family life for her career.'

or

'She sacrificed her career to support him.'

In either scenario, we understand that she suffered a loss, overall. A sacrifice - even if made for good reason - is something painful that makes you poorer.

This is not what offerings mean in the Yijing.

Offerings in ancient China

Offerings were of central importance to ancient China's rulers. Performing offerings and divinations, sustaining a living relationship with the spirits of his ancestors who would care for the people, might be the king's most important job. The calendar is defined by rituals.

The great feasts where the king would 'host' his ancestors were also festivals: the offering is cooked in the great ding vessel, the spirits are nourished by the fragrant steam, and people gather to enjoy the spirits' leftovers. This is what I imagine with Hexagram 45: the offering as a shared social experience, reinforcing the bonds (to one another, to place, to ancestors) that unite people.

There may not be a perfect modern analogue for this, but we can see a connection with our own gatherings, big or small - from sporting fixtures to Christmas dinner - where we participate in shared traditions and remember the dead.

This points to a vital role of offerings: they create connection and relationship - not least among people. There are even a couple of instances in the Yijing where an 'offering' can be interpreted as being made to another human being - 47.2.5, maybe 14.3. We can certainly use the concept of offerings that way in our own readings. Open-source software is a modern offering; so are those apples left out by the roadside just up the road from me, with a sign asking, 'Please take some.' We're all in this together, say the offerings; let's help one another.

Offerings made to the spirits of nature or ancestors say very much the same thing. If you make a sacrifice to the mountain spirits, you are expressing your confidence that they will respond. I don't think you would imagine that you were making yourself poorer.

My modern prejudices are telling me that if you expect something in return for your offering, this somehow cheapens it. But I think my modern prejudices are missing the point. An offering isn't purely transactional, quid pro quo; it's shared. You are sharing your meal with the winds and mountains - or the winds and mountains are sharing their meal with you. If anything, the offering is a celebration of how you are part of a single ecosystem of mutual support.

Only someone wholly immersed in the circulating flow of energy, giving and receiving, could make this kind of offering. And being part of this cycle of goodwill, that circulates through offerings, rain and harvest, is not optional. If the crops fail, you can't step outside the cycle and order a supermarket delivery instead.

Ancient offerings, modern readings

So… a few 'offerings' in readings will be obvious in the context (cooking a meal, giving a concert…). For the many that aren't obvious, it might help to think of an offering as a way of nourishing, investing in and (re-)creating a relationship.

We can think of it in terms of human relationship to start with. Love is a verb. How much can you give? How fully and wholeheartedly will you participate?

Or to put it another way - what are you prepared to spend? Spending our resources for someone or something - time, energy, attention, not just money - is an offering. You might make offerings for your creative work, or for your children - not as an abstract decision, but in your daily actions.

“The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run …”

Henry David Thoreau

I also think it's important that an offering is a ritual. As a ritual, it may or may not involve incense and candles, but it certainly involves attention. So when a reading invites me to make an offering, I need to become conscious and deliberate about what I'm giving and how that works: what does it create, what is it part of? (How does it 'create success'?) Whatever I'm doing can become more intentional. There's more than one way of cooking supper.

The Book of Rites says,

“Sacrifice is not a thing coming to a man from without; it issues from within him, and has its birth in his heart. When the heart is deeply moved, expression is given to it by ceremonies; and hence, only men of ability and virtues can give complete expression to the idea of sacrifices.”

Liji, the Book of Rites, Legge translation.

It's also interesting to reflect on how divination and offerings were originally part of the same ceremony. People would often divine to ask what would be a fitting offering. With an expanded idea of an offering as conscious spending, deliberately nourishing relationship… many of our readings now might be doing the same. We're still asking what to do, what to bring, how to participate… what to offer.

Chinese tigers

Tigers have been prowling through Chinese thought and folklore for many thousands of years. Their meaning is interesting: not just wildness and danger, though of course they might eat you, but also courage and protection against evil - from the wild boar that would eat your crops, and also from demons and evil spirits. Lindqvist writes,

'There are a great many tales about tigers, or rather tigresses, saving people from evil forces and giving their milk to abandoned infants, much like the story of Romulus and Remus and the she-wolf of Rome.'

Small children wore caps or shoes depicting tigers for protection; warriors had tigers on their shields. They also adopted tiger shields and skins to share in the tiger's power and ferocity: 'tiger' was a term of respect for military leaders. And there is the mysterious motif of Chinese bronzes, showing a human figure, quite peaceful, in the tiger's mouth. As far as I'm aware, no-one knows what these represent. The best guess is that they have shamanic significance - passing through the tiger's mouth into a new realm.

Yijing tigers

The tiger appears in three places in the Yijing. First in Hexagram 10 -

'Treading a tiger's tail.

It does not bite people.

Creating success.'

and also in its third and fourth lines:

'With one eye, can see.

Lame, can still walk.

Treads on the tiger's tail:

It bites him. Pitfall.

Soldier acting as a great leader.'

'Treading the tiger's tail.

Pleading, pleading,

Good fortune in the end.'

Then towards the centre of the whole book, in Hexagram 27, line 4:

'Unbalanced nourishment,

Good fortune.

Tiger watches, glares and glares.

Chases and chases his desires.

No mistake.'

And finally, triumphantly, in the fifth line of Hexagram 49, Radical Change:

'Great person transforms like a tiger.

Even before the augury, there is truth and confidence.'

Introducing the tiger: Hexagram 10

The oldest representation of a Chinese tiger is in a burial, where the body is flanked by figures outlined in shells: a dragon to the east, a tiger to the west.

This is at least 5,000 years old - and the positions of dragon and tiger to east and west are those known to feng shui tradition. Tigers are the counterpart of dragons, part of the binary of earth and heaven, female and male, that eventually became yin and yang.

The Yi begins with the flight of the dragon through Hexagram 1. Then Hexagram 2 (where the dragons also show up in line 6) says,

'Fruitful in the south and west, gaining partners.

In the east and north, losing partners.'

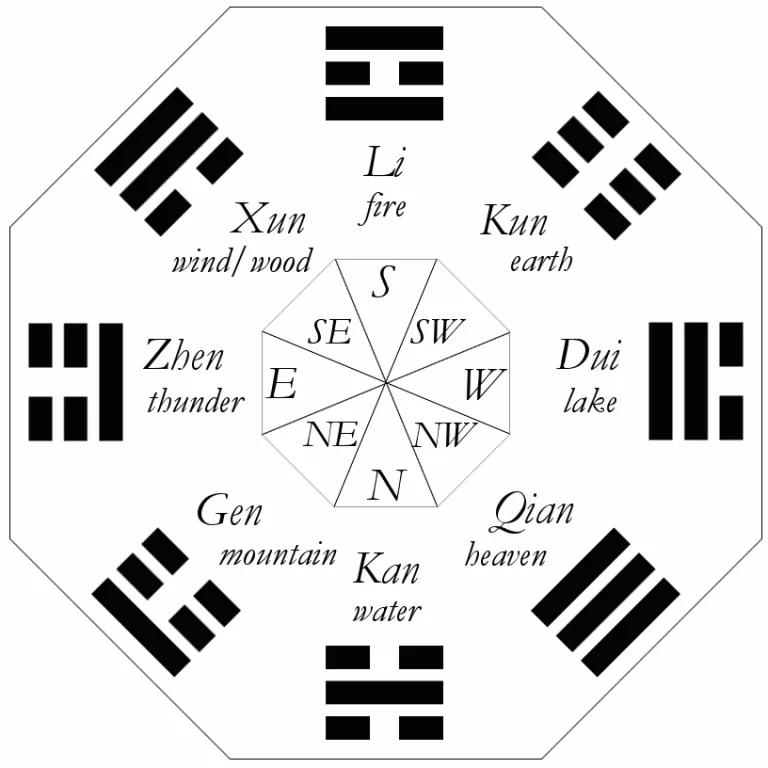

Each point of the compass has its corresponding trigram in the Later Heaven Bagua (which, confusingly, is the oldest arrangement):

The east and north, where you lose partners, are zhen and kan, the constituent trigrams of the very next hexagram, 3, Sprouting. The south is li, fire, which appears for the first time in Hexagram 13, People in Harmony - gaining partners! And west is dui, lake, which appears for the first time in Hexagram 10.

So the tiger appears in the west, just as it did in the Neolithic burial. It stands opposite the dragon of Hexagram 1, just as it has always done, and we have travelled all the way across from Hexagram 3 to reach it. And… could we gain it as a partner?

'Treading a tiger's tail.

It does not bite people.

Creating success.'

You know I like to ask the most simple-minded questions I can come up with about hexagrams and readings (and I can come up with some really simple minded ones!). For instance, why would anyone want to tread on, or near, a tiger's tail? If it bites, you're cat food. Wouldn't it make a lot more sense to go quickly and quietly in the opposite direction?

The combination of those tiger associations - courage, protection, balance for dragon-powers - with reading experience helps to answer the question. People want to get closer to the tiger so they can share in its power and vitality. I've seen this refer to experiences from asking the boss for a raise to visiting a sacred place full of spiritual power. It's about connecting with power, not just as pure idea or inspiration, but here in the real world. So we dance with something that might swallow us whole; we need to Tread with care, to observe the correct rituals -

'Things are tamed, and then there are the rituals. And so Treading follows.'

Sometimes, too, Hexagram 10 can simply be a warning that there is a tiger much closer than you thought: a big, fierce spirit, something you really shouldn't tread on by mistake.

That comes through especially in the two moving lines with the tiger - lines 3 and 4, what's known as the 'human position' in a hexagram - its awkward centre, where we try to bridge the gulf between heaven and earth, ideal and implementation, and don't always manage it. Changing together, these two lines look back to paired hexagram 9, Small Tending. That's a time for careful, small-scale cultivation, preparing the ground, becoming ready to receive the Mandate of Heaven, but not ready yet.

Treading's Small Tending:

'With one eye, can see.

Lame, can still walk.

Treads on the tiger's tail:

It bites him. Pitfall.

Soldier acting as a great leader.'

'Treading the tiger's tail.

Pleading, pleading,

Good fortune in the end.'

Both lines need to be careful: the very first thing to know about the tiger is that this could eat you. It looks like there are two ways this could go: will you be bitten, or blessed? The difference between the two has a lot to do with their zhi gua, the hexagram each line changes to.

Line 3 is not up to the tiger's challenge, though it imagines differently. The 'small image' commentary on the line says,

'"The one-eyed may still see" but not well enough to achieve clarity. "The lame may still tread" but not well enough to keep up. The misfortune of being bitten here is due to one's being unsuited for the position involved. "A warrior tries to pass himself off as a great sovereign" because his will knows nothing but hardness and strength.'

(R.J. Lynn's translation)

This line changes to Hexagram 1 - it has altogether too much dragon energy. It's full of beautiful ideas, but lacks the capacity to live with them, embody them, in practice, and is about to get a nasty reality check.

Line 4 is just beginning to create a better relationship with the tiger, 'pleading and pleading', and this could be the beginning of good fortune (which is coming 'in the end', not right away). There is a powerful, fierce spirit here - maybe protective, certainly not rational. Sometimes it's someone else's, sometimes it belongs to the questioner; either way, it needs approaching with extreme care, and with complete presence of mind.

That presence of mind is found in the relating hexagram for the line: 61, Inner Truth. 'Pleading, pleading' is the voice of inner truth: present, wholly connected between heaven and earth, trusting, vulnerable.

Through the tiger's mouth: Hexagram 27

The tiger's next appearance - and the one that's most powerfully reminiscent of those mysterious bronzes - is in the fourth line of Hexagram 27, Nourishment or Jaws:

'Unbalanced nourishment,

Good fortune.

Tiger watches, glares and glares.

Chases and chases its desires.

No mistake.'

This line changes to Hexagram 21. Who could be better at Biting Through than the tiger? Scott Davis looked back to the fan yao, 21.4 changing to 27, and suggested the 'dried bony meat' of that line is being fed to the tiger, swallowed by the Jaws. For him, this is part of the transformation of boy to young man, passing through the tiger's mouth in initiation.

Also, the line change here creates the trigram li, which represents fire, light and vision, for the tiger 'watching, glaring, glaring'.

This is nourishment that's 'unbalanced' - toppling over, overthrown. It seems quite odd that this should mean 'good fortune': isn't balance and harmony the goal? But the tiger is not looking for balance; it's 'chasing, chasing its desires'. The components of this Chinese word 逐 zhu, chasing, show a foot on the road after a pig - the tiger's desires aren't ambiguous or complicated.

The glaring, chasing tiger means good fortune, not something we should stop, second-guess or try to moderate. The hunger of Hexagram 27 joins with the resolve of Hexagram 21: know what you want, go after what you need, bite through the obstacles. There's more to life than balance.

You can see that a transformation is underway here, compared with the propitiatory caution of Hexagram 10. The natural way to respond to this line, I've always found, is to start to identify with the tiger, experience the intensity of your own desires and be less afraid of them. Good fortune; no mistake.

Becoming the tiger: Hexagram 49

The tiger's appeared at a third line (bad news) and two fourth lines (better…), and now emerges at a fifth line, the place of autonomy and choice:

'Great person transforms like a tiger.

Even before the augury, there is truth and confidence.'

Here as in Hexagram 10, it's in the western, lake trigram - but now in its central line, and the transformation is complete. This tiger is not an external force that might devour you; the great person is making a tiger change of their own.

What exactly is happening here? Tradition says this one is showing their leadership quality, revealing the moral authority to bring about change. Lynn quotes Kong Yingda:

'Such a one may adjust the ways of former kings and establish laws on his own initiative. There is with him such beauty in the manifestation of culture that it scintillates and commands attention. In this he resembles a tiger changing [into its rich, luxuriant winter coat], whose patterns shine forth with great brilliance.'

The great person has fu, truth and confidence, before the augury - the same fu that fed into 10.4 from its connection to Hexagram 61. For us this is two concepts: being confident/trusting, and being trusted/ inspiring confidence. Bradford Hatcher evokes both: 'The tiger does not need to seek out the oracle to ask about his timing… he does not need to worry if others will believe him.' But the Chinese fu is a single idea: complete connection to spirit, bringing the Mandate of Heaven frictionlessly down to earth and into practice, inspiring confidence all the way along.

This line changes to Hexagram 55, Abundance, Feng, where heavenly signs communicate the Mandate, and the leader must act with decision. Hexagram 55 is formed of the trigrams of thunder and fire, initiative and insight - as is Hexagram 21, created by the change of 27.4. (And 49's trigrams? Fire and lake: south and west, where you gain partners.)

This quality of fu also reminds me of the man in the tiger's mouth from the bronzes, both confiding and confident. The great person starts to look like a shaman, putting on the tiger's essence with its skin (Hexagram 49's name also means skinning) and travelling through to another world. (The trigram dui also means opening, creating a way through.)

The 'tiger transformation' in readings is an the experience of being filled with ferocious courage and confidence, becoming your own oracle. I've received this line a couple of times when I asked what I could give someone by reading for them, and always understood it as a good sign.

Yet it's also one of those profoundly, startlingly morally neutral lines. As your tiger-self, you are the ruler of your own destiny, clear and single-minded (just as much as 27.4); your influence shines out as bright as your stripes. The tiger goes his own way, and never has to consider anything or anyone else.

A story?

I think I can see the outline of a story here - one of clarifying the relationship of dragon and tiger, creative spirit and a courage to act that responds to it, like the lake reflecting heaven in Hexagram 10. This relationship flows through fu: centred connection, truth, trust and confidence, the open channel through which spirit and inspiration can flow through into action.

Hexagram 10 begins to open the connection, with cautious treading, rituals to learn, alignment to create. Just drawing directly on the ideals and inspirations of dragon-mind - 10.3 changing to 1 - is not enough; we need Inner Truth and open-hearted pleading.

Then comes the central passage through the Jaws of Hexagram 27, where receiving line 4 encourages you to look inside yourself for the tiger.

And finally the tiger transformation at the peak of Radical Change - where the only tiger present is the great person - putting on the tiger as a new self and creating the right relationship of heaven and earth.

That's something I asked Yi recently, and it answered with Hexagram 23, Stripping Away, changing at lines 1 and 6 to 24, Returning -

I think this is a lovely, fascinating, satisfying reading, so I'm sharing a few thoughts on it with you for this episode of the podcast. I hope you enjoy it!

(If you'd like to have a free reading on the podcast, you're very welcome to book one here.)

An update…

Just after publishing this episode, I was sorting through some foraged chestnuts when I found the one whose photograph you can see above. I didn't roast it; I'm going to take it with me on my next foraging walk to the local woods and tuck it into the leaf litter.

I Ching Community

Podcast

Join Clarity

You are warmly invited to join Clarity and –

- access the audio version of the Beginners’ Course

- participate in the I Ching Community

- subscribe to ‘Friends’ Notes’ for I Ching news