The I Ching’s two ingredients are two kinds of line:

![]() broken (yin)

broken (yin)![]() and solid (yang)

and solid (yang)

These are the deep roots of a traditional Chinese idea: the relationship of yang and yin gives rise to all that is.

Yang and yin aren’t fixed; they’re ways of relating, and they only exist in relation to one another. You can see that this is true from the modern Chinese characters for yin 陰 and yang 阳: yin shows the shaded side of a hill, yang shows the sunny side. You can’t have half a hill, and you can’t have yin without yang or yang without yin.

Yang is dynamic, it starts things and drives them forward; it’s bright and vivid; it acts. Yin is more passive, receiving and responding; it’s dark and open; it is acted on.

Building with lines

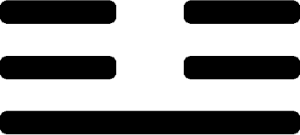

These two kinds of line are stackable – they build up into hexagrams, groups of six lines, like this:

The energy flows upwards through the lines of a hexagram, from the bottom line to the top: you could think of them as footprints, visible signs of the way everything is moving.

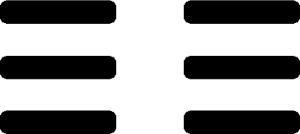

And you can also understand a hexagram as the relationship of two natural energies, painted in trigrams – groups of three lines, like these two:

and

There are 64 different hexagrams, which work more or less like ‘chapters’ of the Yijing. Each hexagram and line is melded with its own words, and the whole is woven together in a dynamic structure like a living cathedral.

When you ‘consult the I Ching’, all you’re doing is casting one of these hexagrams.

For example…

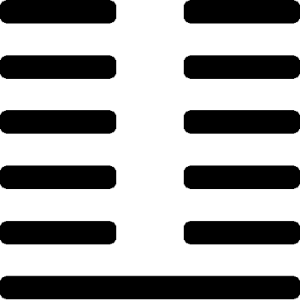

The 24th hexagram represents return and rebirth: any situation that is completely turned around and begins afresh. The yang energy of light and initiative is represented only in the first, bottom line: it’s just beginning to enter the situation. There is a tradition that this hexagram represents the winter solstice, the darkest moment of the year that is also the moment when light begins its return.

The dark, quiet yin still dominates the situation: this isn’t an instant return, like flicking a light switch, and people who receive this hexagram are often feeling impatient. But the yin lines are open to welcome the returning yang: they offer no resistance. You can see how in time it will grow and surge up through the hexagram.

Each hexagram has its name – this one is called Returning – and associated Oracle text. This one reads,

‘Returning, creating success.

Going out, coming in, without haste.

Partners come, not a mistake.

Turning around and returning on your path.

The seventh day comes, you return.

Fruitful to have a direction to go.’

This book will speak to you

There are hundreds of translations of the Yijing, all striving to capture the richness and simplicity of the original ancient Chinese. The Yijing’s words paint vivid miniatures, tell stories, give advice, subtly allude to myth and history. And they’re enriched by strong connections to their ancient image-roots.

This means that if you’re drawn to word-painting and story-telling, talking with Yi will come naturally to you. But the same is true if you’re fascinated by structures, or images, or movement. Its visual imagery speaks to artists; its words speak to poets; its rhythms speak to musicians and dancers; its structures speak to engineers. No matter how your imagination works, it will work in conversation with the Yi.

And this is the real reason why people have been coming to Yi for help for some 3,000 years: it draws you into conversation. People experience it more as a person than as a book. Nor is this some fluffy new-agey notion. The Great Treatise (from around 200BC) says,

‘Yi is a book that cannot be far away. Its dao is ever-changing. …It gives warning without and within, shedding light on trouble and its causes – not as a commander or guardian, but as if mother and father drew near.’