There is danger: fruitful to stop

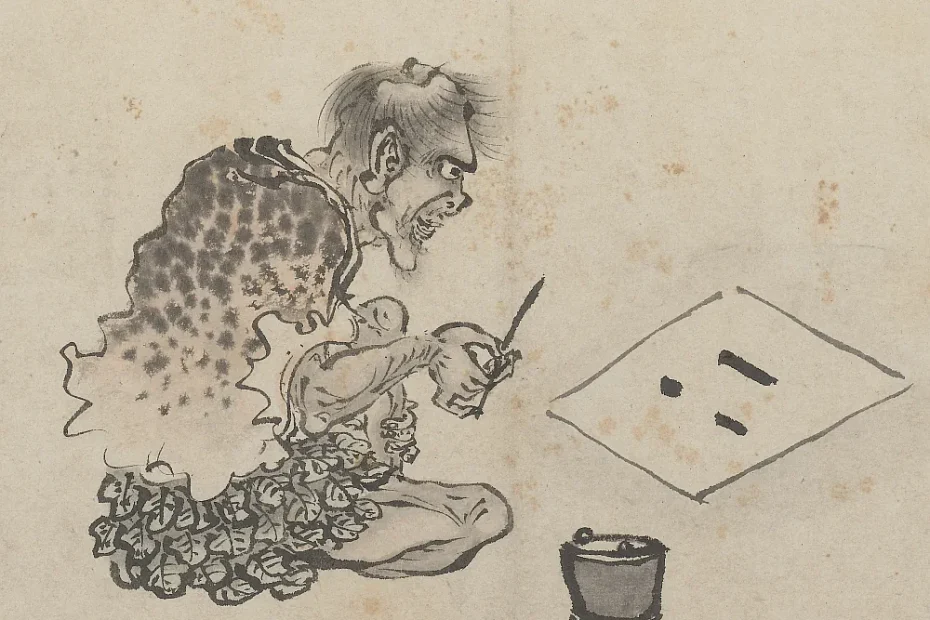

I wrote a bit before about the dangers of AI interpretation that it might, as 26.1 says, be fruitful to stop: its inaccuracy with hexagrams and text; the peril of having an interpretation handed to you without ever engaging with the imagery yourself; and finally, its lack of emotional engagement.… Read more »There is danger: fruitful to stop