There’s more than one story of the Yi’s origins…

Mythical origins

The story begins in the 29th century BCE with Fuxi, China’s first emperor, who may have had the body of a serpent. It was through his insight that the trigrams were discovered, and people could begin to understand their world:

“In high antiquity, when Fuxi ruled the world, he looked up and observed the figures in heaven, looked down and saw the model forms under heaven. He noted the appearances of birds and beasts and how they were adapted to their habitats. He examined things in his own person near at hand, and things in general at a distance. Hence he devised the eight trigrams with power to communicate with spirits and classify the natures of the myriad beings.”

This story comes from the Dazhuan, the Great Treatise (in Richard Rutt‘s translation), which is part of the Yijing itself. In another version, the trigrams were inspired by the markings on the back of a dragon-horse that emerged from the Yellow River – but I find the Great Treatise’s version the most resonant and eloquent. We can all still look at our own bodies and the natural world and see trigrams.

At least a millennium later – maybe two – the future King Wen of the Zhou (1152–1050BCE) was imprisoned by the Shang tyrant Zhouxin. During his imprisonment, he combined the trigrams into hexagrams, and gave the hexagrams their names. After his death, his son the Duke of Zhou added texts to the moving lines.

And Confucius (551-479BCE), a faithful student of the wisdom of early kings, wrote the Ten Wings – all the commentaries that have become part of the Yijing we know, such as the Image text describing the noble one’s response to a hexagram’s trigrams.

So the story unfolds naturally, from simple trigrams through hexagrams to changing lines and finally the addition of the Wings.

(A much fuller version of this story – the most vivid and colourful one I’ve read yet – can be found in the introduction to Benebell Wen’s I Ching.)

Historical origins

The history of the Yijing’s origins, as it’s been pieced together from archaeological records and textual analysis, is – unsurprisingly – altogether more mysterious and less clear than its myth.

The earliest records of divination in China, dating from the Shang dynasty (c.1600-1046BCE), are of pyromancy: divination with fire. Tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae were carefully prepared, drilled and cracked by the application of heat. The cracks could be interpreted by the king – mostly, it seems, to give direct ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers on questions of policy (would there be good weather for a hunting expedition? was now the right time to open this field for ploughing?), though sometimes with a little more detail. The questions and sometimes also the oracle’s responses were inscribed on the bone and kept as records. It’s not clear whether the bone oracle was a direct ancestor of the Yi – perhaps it’s more of an older cousin.

But there are also records of a counting oracle in the Shang: people recorded series of six numbers that had ‘spoken’, like a cracked bone could ‘speak’. If you’ve ever cast a reading with yarrow stalks or coins, you’ve joined this tradition: generated a series of six numbers, paid attention to their pattern and listened to what it has to tell you. The numbers used have changed, but the basic principle of differentiating odd numbers (which we call ‘yang’ lines now) from even (‘yin’) is ancient. Were the Shang already sorting and counting yarrow stalks? We have no way of knowing.

The oracle we recognise as the Yi was brought together in the early years of the Zhou Dynasty, around 800 BCE. Hexagrams, those series of six numbers, now had names and associated text that anyone could learn. The text was drawn from many sources: sayings, song, legend, myth, maybe divination records for the hexagram or line. (WikiWing has its roots in a long tradition!)

The Zuozhuan has several early records of divination with Yi, which hint at how it was spread across the kingdom by travelling diviners and became more widely known, working its way into people’s language and understanding. Over the centuries, as people added their reflections, experience and commentaries to the core text, it became recognised as a book of wisdom. And in 136BCE, the Yi along with its Wings was one of the five core texts, the Wujing, identified as underpinning all Chinese thought.

(The more recent reprints of my book – 2018 and 2021 – have a fuller historical introduction. It doesn’t include all I wanted to, as it had to be cut by about 30% for publication, but Change Circle members can download the original, uncut version from the Change Circle Library.)

A ‘fact check’

So, what of the mythical version?

Were the trigrams in use for millennia before they were combined into hexagrams? I don’t know of any evidence for that – though it does look as though hexagrams have long been understood as interacting trigrams. (The Fuxi bagua or Early Heaven Arrangement of the trigrams, though, is not ancient – it’s considerably younger than the Later Heaven arrangement, as Harmen Mesker explains.)

Are hexagram names and texts a generation older than changing lines? Maybe. Fragments of the Guicang, traditionally said to be the hexagram oracle of the Shang dynasty, have been discovered – and they contain hexagram texts but nothing resembling a line text. Intriguingly, the hexagram names of the Guicang are very often the same as those in the Yi, even though the text that follows is completely different. The same hexagram is named ‘Marrying Maiden’, for instance, but what follows is the story of Heng E stealing the elixir of immortality and fleeing to the moon.

Did King Wen name the hexagrams and write the oracles? Did the Duke of Zhou write the line texts? How would anyone know? (It’s worth noting, though, that the Great Treatise itself doesn’t attribute the text to them, simply to ‘sages’, and you’d think that if their authorship had been commonly accepted at the time, they would have been given credit.)

And did Confucius write the Wings? No – but plenty of his wisdom found its way into them.

Beyond the ‘fact check’

…there’s an oracle whose origins no-one can pretend to understand.

Who first realised that strings of three or six numbers had meaning? Or discovered if you put a question to the spirits and generated a ‘random’ series of numbers, your question would be answered?

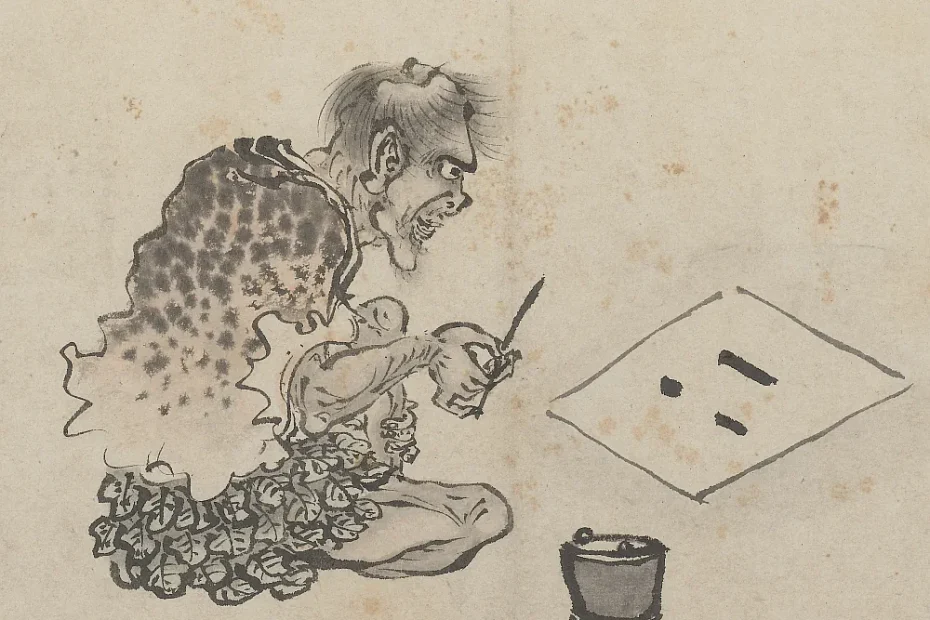

How did they know that – for instance –![]()

meant ‘marrying maiden’ specifically, or that

![]()

meant ‘abundance’?

Who had the insight that these numbers/lines might be changing?

How did they not only name single hexagrams, but create a complete matrix where any hexagram can change into any other – and the nature of that change is captured in the moving lines?

(And not just when the hexagrams differ by one line, but multiple lines? Imagine trying to create something that complex…)

And while we’re asking, how come casting coins at random delivers a meaningful answer?

(I’m fairly sure the archaeological technique to answer these has not been invented yet.)

Dear Hillary, Please note for your readers attention that a considerable amount of I Ching information including scientific research work can be found on the following domain websites:- ichingmaster.co.uk; ichingmaster.uk : ichingmaster.info. in addition to which all my I Ching books with the exception of volume 8 can be downloaded from Google play books or if required Electronic CD rom editions directly from Compton/kowanz publications or myself. For your own interest :- regarding linear trigram lines:-

A positive line to a negative line may be represented as = 9: A positive line to a positive line may be represented as = 7

A negative line to a positive line may be represented as = 6: A negative line to negative line may be represented as = 8

So where are the first five numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ) and what do their linear lines represent? The answer to that question can be found in volume 7 of my research work – The Lost Companion of the I Ching Classic – The T’ai Hsuan Ching which consist of 81 Tetragrams (four linear line symbols).

Kind Regards

John.