On not knowing the first thing about the Yi

Back in 2015, I titled a post, ‘I don’t know the first thing about the Yi‘. By this I meant not knowing how it came to be – how people first knew that a certain pattern of lines belonged with certain words.

Well… I still don’t. But some people say they do, which is interesting.

As before, I’m still not convinced by the tradition dedicated to ‘explaining’ the text’s imagery through trigram associations. Despite its antiquity, this still strikes me as a very erudite, determined and ingenious game of ‘Pin the tail on the donkey’ – or pin the trigram association on the text. It doesn’t give rise to ‘aha!’ moments for me; it doesn’t stir the imagination or cast light on the meaning.

Hexagram pictures

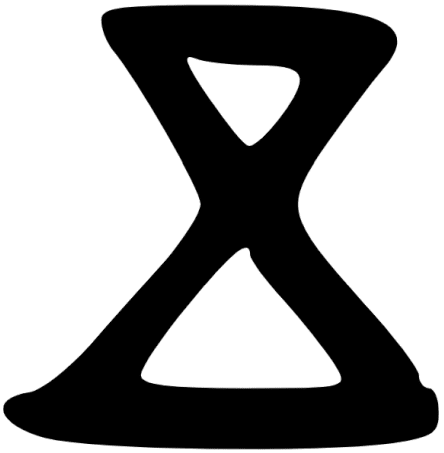

Much livelier (and, it turns out, not unrelated) is the idea of hexagram pictures. We’re all familiar with the idea that Hexagram 50 is the image of a vessel, with feet, body, handles and carrying-rod at the top:

The same is true of Hexagram 27, a picture of an open mouth –

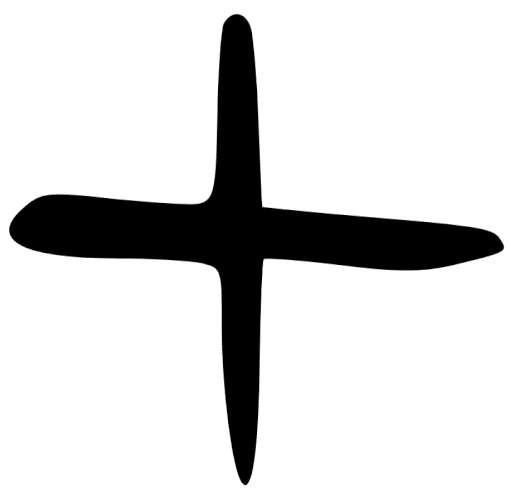

and Hexagram 62, the flying bird seen from below –

The Tuanzhuan – the commentary on the Yijing that constitutes its first two Wings – even says explicitly that ‘Ding [Hexagram 50] is an image’ and ‘The hexagram has the form of a flying bird’ for Hexagram 62.

I know of two people (Thomas Hood and Sakis Totlis) who seized on this idea and ran with it, concluding that every hexagram represented one (and only one) picture, and this was its one true original meaning. But the two of them saw different pictures in almost every hexagram. With the possible exception of Hexagram 50 (more on that below!), there isn’t just one picture per hexagram.

To take another example, one that Bradford Hatcher pointed out to me, the Yi mentions turtles three times, in hexagrams 27 and then also in 41 and 42:

Those are three of the four hexagrams that have a soft centre, or inner space, of broken lines contained within hard outer ‘shells’ of solid lines. This doesn’t indicate that these three hexagrams mean ‘turtle’, or that they’re intended as pictures of turtles. (Like I said, Hexagram 27 is a picture of an open mouth, too.) Only that at some point, perhaps, they reminded someone of a turtle.

An ancient hexagram picture (and how it was drawn)

This post’s inspired by two articles by Adam Schwartz: ‘Between numbers and images: the many meanings of trigram li in the early Yijing’ and ‘Between numbers and images: the many meanings of trigram gen in the early Yijing’. They make for fascinating reading.

To start with, seeing Hexagram 50 as a ‘hexagram picture’ of a vessel is not just a post-hoc rationalisation invented by the Tuanzhuan authors (or perhaps their interpreters, as they might have meant that the vessel was an image, not the hexagram by that name). The association is more or less as ancient as the text itself.

The evidence for this is found on a dagger axe dated to the 8th century BCE. Its inscription includes text from Hexagram 50 along with the hexagram itself, deliberately written to resemble the character ding as closely as possible.

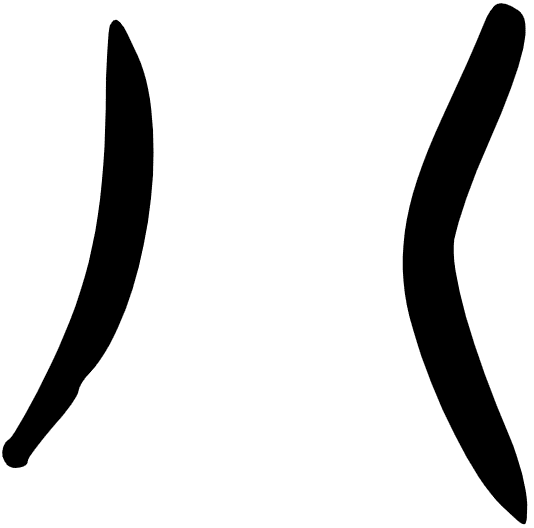

Hexagrams at this time were written down not as we do now, as two kinds of line, but as stacks of the numbers cast. No need to remember which number corresponded to which kind of line: the number was the line.

A solid line would be 1, or sometimes 7 or 5 –

A broken line, then as now, could be 6 or 8 –

Some numbers were simplified to make them more unambiguously recognisable in these vertical stacks: the number 5, for instance, would be written without its horizontal lines to avoid confusion with adjacent ‘1’s; ‘6’ became more like an inverted ‘v’. A few more simplifying steps would bring us to the ‘modern’ (!) way of drawing a hexagram.

At the top of page 69 in Schwartz’s article, you can see how the legs of the ‘6’ in the first place of Hexagram 50 have been deliberately curved to resemble the legs of the vessel in the character ding. It’s impossible not to see that the person who wrote down this hexagram had in mind that it created a picture. And the sheer antiquity of this inscription makes it – at the very least – highly likely that the authors of the Zhouyi text had this in mind, too.

It’s good to know this way of writing lines as numbers, because it makes the hexagrams much more obviously pictorial. When you write the trigram li as 1-8-1, with the lines close together, it’s not hard to see why the Shuogua identifies it with creatures with shells.

Pictures in hexagrams

Schwartz has more to say and bigger claims to make, though. The Shifa manuscript (from the fourth century BCE) describes a method of divination from seeing pictures in trigrams, bigrams and even individual lines. He evokes a divinatory tradition and skill of seeing these images in hexagrams, too – not just each hexagram corresponding to one picture, but multiple pictures in a single hexagram, new and different in each reading. (You can imagine that the picture might vary depending on which number you cast – a 5 or a 1, perhaps.)

And here Schwartz maintains he does know the first thing about the Yi: he says that these pictures are the origin of the Zhouyi text: ‘Hexagram pictures began as numbers, and …hexagram pictures contain the images that led to the composition of the Zhou Yi’s text.’ Individual diviners’ impressions of the pictures in readings would be codified into lore and into the individual hexagram and line texts.

For Schwartz, the Shuogua, ‘Discussion of the Trigrams’, the Yi’s eighth Wing, is an example of this trigram-image lore. So its lists of trigram associations are not arbitrary, but begin with the pictures diviners could see in numerical trigrams and associations developed from there. (This is clearer for some than others!) The Shuogua would have been intended as a handy reference for use not only with the Zhouyi, but also with other divination manuals that used trigrams and hexagrams, and some of its associations belong to those other traditions. (I would add that the whole idea of needing to look up trigram associations in a separate source indicates you are probably working with a book that doesn’t have its own text for each hexagram and line. I’ve always had the feeling the Shuogua was a somewhat distant cousin of our Yi.)

It seems to me this has the potential to bring trigram associations to life. Using them would not be a matter of trawling through a shopping list of stuff for something that fits your ideas, but of looking directly at your cast hexagram: what does it look like to you, today? Variation would be natural. Schwartz writes, ‘Diviners and users saw different images in the same picture, and saw the same image or similar images in different pictures. To make all variation equal the text of one tradition (i.e. the received text tradition) betrays the overall tradition.’

(Well, that would be one way of looking at it. Another would be to say that respecting the words the Yi speaks to you honours the wisdom of those who crafted the text we received, and its own immense, living tradition.)

… and characters in hexagrams

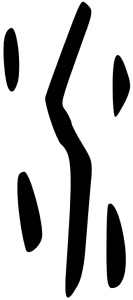

Another interesting point, made plain by that dagger axe, is that this isn’t just about what object a trigram or hexagram resembles, but – primarily – what character. The trigram kan, for instance: its name, kan, means ‘pit’, so why is it the trigram of running water?

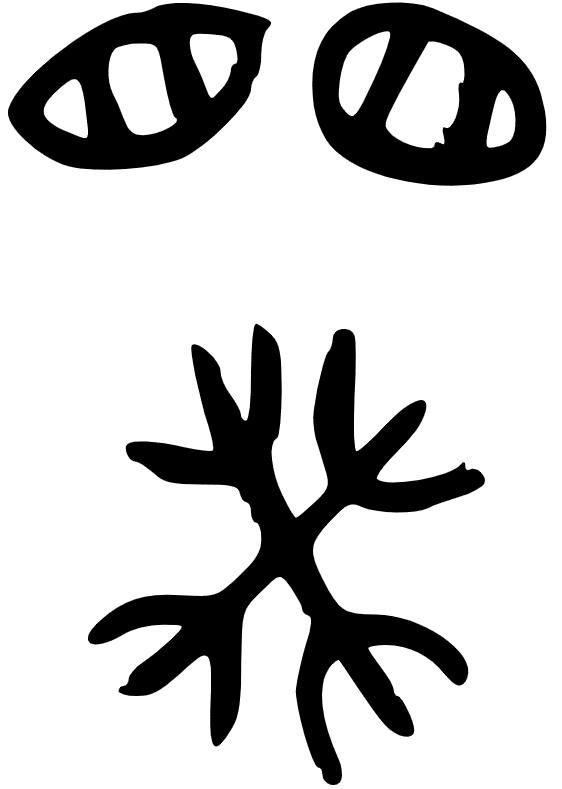

This gives hexagram pictures a lot more descriptive power: they can represent more abstract ideas as well as concrete objects. Have a look at Hexagram 38 and its name:

You can see two ‘eyes’ in the two li trigrams this contains – and how (compared to the symmetry of Hexagram 30) one eye is misaligned to represent the squinting, ‘seeing differently’ of gui. The crossed lines at the bottom of the character, probably a mat for offerings, correspond to the lowest lines of the hexagram – or perhaps just to the first line, if we imagine it drawn as a ‘5’.

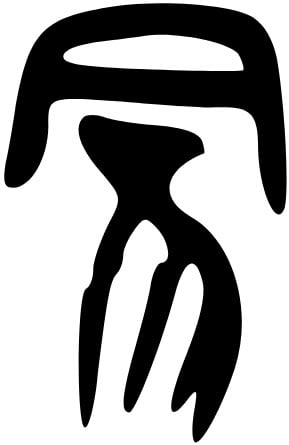

Or take Hexagram 4, where ignorance and clouded vision are represented by a character that shows a pig covered over by vegetation, meng 蒙:

The covering vegetation in the character corresponds to the covering gen trigram in the hexagram. (Kan, the inner trigram, is also said in the Shuogua to be a pig – one of those associations that’s not so obvious.)

So… is this it? Do these pictures explain how the text was written?

Exciting examples…

Schwartz’s two articles have some really exciting, persuasive examples. The strung fish of 23.5, for instance, suspended from line 6 (the trigram gen is an all-purpose picture of things that hang down), and maybe visible as a stack of overlapping ‘6’s (inverted ‘v’s). (He suggests fish scales for these, but to me it looks more like fish skeletons.) Or the range of meanings for the character jie – ‘boundary’, ‘separate’, ‘inbetween’, ‘chainmail’… – and its connection with the trigram kan. (I’m bound to be impressed by this one, of course, as I’d spotted it myself.) Or the lovely idea that in Hexagram 31, Influence, the lower trigram gen is like a hand feeling its way up the body of dui.

…and donkey tails

Unfortunately, picture-spotting can easily devolve into the old game of trigram associations. It’s helped along partly by ignoring whatever doesn’t fit, and partly by allowing very liberal correspondences: trigrams, nuclear trigrams, variants of trigrams (any number of yin lines enclosed by yang corresponding to trigram li, for instance), inverted trigrams (zhen for gen) and maybe their opposites, too.

(I’ll pick just one example of selectivity so you see what I mean. Li, a footnote explains, represents the belly, and hence ‘big-bellied earthenware’ as in 30.3 and 61.3 (61 being a giant, redoubled li trigram). There’s a fou jar to drum on in 30.3; 61.3 actually just has a drum, but I wouldn’t quibble at that – the shape is the same. There is another fou jar in the text, though, at 8.1. He doesn’t mention that one.)

You can read Schwartz’ articles for yourself (find them on his Academia.edu page) and see what you think.

How the oracle got its voice?

Finding pictures isn’t going to tell us how the Zhouyi’s authors knew which image should go with each line. It makes sense to see a turtle in Hexagram 27, but that brings us no closer to understanding why the turtle should be mentioned specifically in line 1, let alone why it’s being forsaken. Schwartz himself isn’t especially interested in the received text as a complete work – he’s more drawn to the idea of a skilled diviner who could ‘see’ the relevant images in the moment.

The Zhouyi has grown into more than just a picture book consulted with a trigram reference, though. Its hexagrams as we write them now may not make such vivid pictures, but they do make pure energy patterns: you can feel the energy surging upward through 34, or contained by outer trigram gen, or integrating perfectly when gen meets dui in Hexagram 31.

And beyond that, it has a structure, a whole web of interconnections, that extends way, way beyond individual hexagram components. (To understand the uneaten fruit of 23.6, it certainly can’t hurt to see the picture of ‘things that hang down’ in the trigram gen. But it also helps to imagine where it will fall, in the relating hexagram 2, and the paired line 24.1.)

And it has a voice.

Enjoy the pictures

However, seeing pictures in hexagrams is still a natural part of divination. No-one needs to study the Shifa manuscript to know this. This isn’t about finding origins for the text, let alone the One True Meaning of a line – just seeing whether a reading of yours looks like a picture.

For example…

Decades ago, probably before I’d even heard of the Shuogua, I asked about something I’d lost and received Hexagram 20. It pointed me to my desk – one of those with a deep top resting on two columns of drawers.

When I cast Hexagram 1 with the fourth line changing about a lost book, Harmen Mesker (who has studied the Shifa manuscript, of course) saw the hexagram as a picture of a stack of similar objects, high up. The book I was looking for was in the middle of a stack of several copies of a different one, on top of a bookshelf.

When a Clarity member with an aching tooth asked ‘What if I try to save it?’ and received 12.4.5.6 to 2, Trojina saw a picture of extraction. And sure enough, the tooth needed to be pulled in the end, with the dentist saying it had too many problems to be rescu-able even with a root canal. (This was a Reading Circle reading – Change Circle people can see the story here along with a discussion of picture-readings – but the reading’s owner kindly agreed to let me use it as an example.)

We may still not know the first thing about the Yi, but then we don’t really need to: it’s still showing us pictures, talking to us, telling us stories – always drawing us into conversation, one way or another.