The character yue, a ‘summer offering’, is one of those interesting ones that appears three times in the Yi:

‘Being drawn. Good fortune, no mistake.

Hexagram 45, line 2

With truth and confidence, it is fruitful to make the summer offering.’

‘With truth and confidence, it is fruitful to make the summer offering.

Hexagram 46, line 2

No mistake.’

‘The neighbour in the East slaughters oxen.

Hexagram 63, line 5

Not like the Western neighbour’s summer offering,

Truly accepting their blessing.’

Two lines within a hexagram pair, Gathering / Pushing Upward, repeating the same phrase, and then a different reference away at the end of the Sequence. What might be learned from reading these three together?

A summer – or spring – offering

In an age of supermarkets, it may not be obvious to us that spring and early summer are seasons of hardship. The stores you depended on through the winter are running low, and there’s little or nothing yet to eat from the garden or fields. English children would eat the new hawthorn shoots, optimistically named ‘bread and cheese’, to get some greenery. And in ancient China, this was the time for an offering.

I’ve seen yue called both a spring and summer offering; the dictionary tells me it was a spring offering originally, in Xia and Shang times, and became a summer offering for the Zhou. Which is it in the Yi? Rutt and Field say summer; Wilhelm goes to the heart of the matter by simply calling it a ‘small offering’. Whether in spring or summer, you would not have much to spare – but you make the offering anyway. As you begin the work of the farming year, you need the spirits’ support.

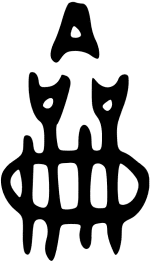

There are two components to the character yue 禴 . The left-hand side means ‘altar’ and is used to identify words to do with the spirits; the right-hand side, 龠 , shows a double flute. It means both the flute and also an ancient measure of volume. Both of these – the measure and the flute – seem significant.

The measure was a tiny one: around 50ml, say the dictionaries, or 1200 grains of millet. (Did somebody count them?) This is a small offering, from small resources – of plant matter only, without sacrificing animals.

Music (which never runs out) is an important part of the rite, played on this double flute. Many early versions of the character show a single mouthpiece, making it possible to blow into both tubes at once: this flute plays chords, creates harmony by itself. The Shuowen specifies that this is a flute with two tubes and three holes, and that playing it ‘makes it possible to bring all sounds into harmony.’

Thinking of this flute – one open mouthpiece, two solid tubes, three open holes – here are the two hexagrams where the word first appears:

45.2 zhi 47

‘Being drawn. Good fortune, no mistake

Hexagram 45, line 2

With truth and confidence, it is fruitful to make the summer offering.’

‘Drawing’ – the same word as in 58.6 – is 引 yin, and literally refers to drawing a bow: the old character shows a bow and bowstring. Hence it means pulling, attracting and stretching, leading on and encouraging, and drawing out, prolonging.

In theory, this line could just as well be understood in the active voice – ‘drawing’ rather than ‘being drawn’. But line theory gives rise to the idea that this yin second line is ‘being drawn’ by the yang fifth line, and experience agrees. People receive this line when they’re being drawn into involvement, or a relationship, or a course of action, or simply when their attention is being pulled to where it’s needed. This hexagram’s Gathering of energy is exerting a kind of magnetic attraction, ‘drawing’ line 2 outward.

This is good fortune and – a reassurance we need in every line of Hexagram 45 – ‘no mistake’. Why might we think it was a mistake? The clue could be in the zhi gua of the line: 45.2 changes to Hexagram 47, Confining. Its name means oppression, isolation and also poverty. How does Gathering respond to this? With yue, the modest offering made from scarce resources. It will bear fruit provided it’s made with fu: with sincerity, confidence and trust.

‘Being drawn’, you’re under tension because you’re pulled to make this offering – drawn out of your own straitened circumstances to your true relationship with the spirits, and toward your hopes for a good harvest later in the year. Experiences with the line often show this forward and outward pull, towards relationship or deeper connection, or really anything except crouching in the pantry counting how many jars you have left.

46.2 zhi 15

‘True and confident,

Hexagram 46, line 2

And so it is fruitful to make the summer offering.

No mistake.’

The paired hexagram, Pushing Upward, repeats the same text:

孚乃利用禴

‘Truth, and-therefore fruitful to make (use of) yue.’

No need to be ‘drawn’ here: this is a yang line, part of the growing shoot below the earth in this hexagram’s trigram picture, with its own stored energy ready to push upward and participate at a higher level. The whole hexagram suggests climbing to make an offering at a high place – like the king at line 4, making offerings on (or to) the sacred mountain of the Zhou, Mount Qi.

Spectacular sacrifices are not called for, only small offerings made with an undivided heart. Legge’s translation makes it explicit:

‘The second NINE, undivided, shows its subject with that sincerity which will make even the (small) offerings of the vernal sacrifice acceptable.’

This line points you towards Hexagram 15, Integrity and Modesty, fitting for an unostentatious offering. I wrote about this one some years back:

‘It helps to think of rank as not just an empty bureaucratic status-label, but in its ideal sense of a true measure of your personal capability. Then this becomes an offering that’s naturally proportional to what you can give – and you can see the connection to Hexagram 15, Integrity. With a completely clear sense of yourself – both your limitations and your potential – you can make a true yue offering. It’s your personal call to the spirits (see the fan yao, 15.2) and you – not any external standard – are its measure.’

From ‘Steps through Hexagram 46‘

63.5 zhi 36

‘The neighbour in the East slaughters oxen.

Hexagram 63, line 5

Not like the Western neighbour’s summer offering,

Truly accepting their blessing.’

The Shang and Zhou were neighbours: the Shang to the East, the Zhou to the west. The Shang were wealthy and powerful, and made ostentatiously grand sacrifices. The Zhou, smaller and poorer, might only manage a small offering, but nonetheless, it’s theirs that receives the spirits’ blessing.

This line joins with Hexagram 36, Brightness Hiding – another story of virtue oppressed by the corrupt Shang regime. But such light is only hidden, never extinguished.

As Harmen points out, there’s an extra character here: not just yue, but yue ji, 禴祭, the summer-offering sacrifice. He suggests this means that only this line refers to the offering; the others mean the musical instrument, which is being played in a different ritual. I think it’s more likely that sacrifice is mentioned here to mark up the contrast with the Western neighbour, who merely ‘slaughter oxen’. The context makes clear that this was for a sacrifice, but the choice of verb seems derogatory: the Zhou perform a named rite from their modest resources, while the Shang seem to think their problems will go away if they just throw enough oxen at them.

I also wonder – and this is pure speculation – whether the character 實 shi, translated ‘truly’, might not be part of the description of the offering. This is the same word as in the Oracle of Hexagram 27 and the second line of Hexagram 50, where it means ‘something real’, substantial and genuine: the vessel contains real substance; you seek something real to fill your mouth. So I think it carries more meaning than just a slight emphasis on ‘receive’.

Looking at this line word-for-word

‘… not like the Western neighbour’s yue offering real-substance receive its blessing’

Are they ‘truly receiving blessing,’ or could this be read as ‘a yue offering of real substance – they receive blessing’?

Also, 實 shi could mean fruit or seed. Fruit is one thing you would not have to offer in spring or summer, of course, but a yue offering of seed?

This line stands at the height of Already Crossing, where we can imagine the Zhou already crossing the river into Shang territory, already founding their dynasty.

‘Already across, creating success.

Hexagram 63, the Oracle

Constancy yields a small harvest.

Beginnings, good fortune – endings, chaos.’

The Oracle reminds us of what happened to the Xia and Shang: they began well, but fell into chaos in the end. Beginnings, good fortune: an offering for spring or summer, one that looks forward to the harvest; tiny seeds have more value, more spiritual reality, than full-grown oxen.

Connections?

The references to yue in Gathering and Pushing Upward are obviously connected: the hexagrams are a pair, and the same text is quoted in both. But is there a substantive connection to the quite different text of 63.5 – are we ‘meant’ to remember those lines when we cast this one?

I think we probably are, for a few reasons.

Already Crossing comes at the culmination of the Zhou story and the Yijing Sequence: now, they are crossing the river and taking up the Mandate. At such a time, they need to reconnect with their spiritual roots: the simple, forward-looking offerings, the gathering at the temple and the ascent to Mount Qi.

The lines in 45 and 46 both advise making use of the yue offering; in 63.5, the offering is crowned with ‘receiving blessing’. The earlier lines emphasise the petition, but this one tells the whole story, from petition to response – from Brightness Hiding to blessing. Maybe it’s as if the early offering were not so much asking for a good harvest as expressing trust and gratitude. (Bradford Hatcher’s take on this line: the Shang say ‘please’, the Zhou say ‘thank you’.)

And finally, the line positions. It’s actually a bit odd that those two lines should share the same text, because structurally, they’re not the same line. To clarify…

‘Maybe increased by ten paired tortoise shells,

Hexagram 41, line 5 and Hexagram 42, line 2

Nothing is capable of going against this.

From the source, good fortune.’

‘Maybe increased by ten paired tortoise shells.

Nothing is capable of going against this.

Ever-flowing constancy, good fortune.

The king uses this to make offerings to the supreme being: good fortune.’

41.5 and 42.2 share text and are paired lines – the ‘same’ line in the hexagram shape, just seen from the opposite perspective. The same is true of 43.4 and 44.3 (‘thighs without flesh, moving awkwardly now’) and 63.3/ 64.4 (stories of attacks on Demon Country): the lines that share text are paired lines.

(The other exception to the rule is 11.1 with 12.1 – but that’s an unusual pair, complementary as well as inverse, so there is a sense in which lines in the same position map onto one another.)

So… why should 45.2 be echoed in the second line of 46, and not the fifth? Perhaps because these two second lines are reaching out all the way to another fifth line, out across the river, and 45.2 is ‘being drawn’ further than we thought.