If you try for an ‘eagle’s-eye view’ of the Yijing, you get to admire its architecture: the intricate connections between hexagrams, the Sequence, two-line changes and so on. What if you zoom in, instead, for a mouse’s eye-view? Here’s an example of that.

I’ve translated Hexagram 4’s Oracle like this:

‘Not knowing, creating success.

I do not seek the young ignoramus, the young ignoramus seeks me.

The first consultation speaks,

The second and third pollute the waters.

Polluted, and hence not speaking.

Constancy bears fruit.’

告 Gao, ‘speaks’ means to announce or inform. It could also mean a more performative announcement, such as making a ritual report to Heaven or the ancestors, but the basic idea is simply that the voice of this text (often, though not always, the Yi itself), when consulted, will speak – or, if questioned again and again, it won’t.

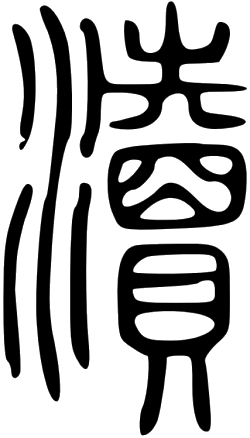

Why not? Because this repeated questioning ‘pollutes the waters’. This may be a bit of a poetic over-elaboration of another single Chinese word, 瀆 du.

Here are some other ways du is translated:

- Harmen Mesker: ‘excessive’

- Schilling: ,verschmutzt’ (soiled, polluted, dirty)

- Rutt and LiSe Heyboer: ‘confusing’

- Wilhelm and Minford book I: ‘importunity’

- Lynn: ‘violation’

- Bradford Hatcher and Geoffrey Redmond: ‘disrespect’

- Minford Book II: ‘insult’

There’s a mix there, but you can see the core ideas: confusion and disrespect. It all fits well with the dictionary definitions: to lack respect, to profane, to take liberties; to importune with repetition; disorder; covetousness, avidity.

The word has another meaning, though: a ditch, drain, sluice or gutter. The left-hand part of the character, generally described as its significant part (the part that conveys the meaning as opposed to just the sound), represents water:

And this awakens our interest, of course, because the inner trigram of Hexagram 4 is kan, which also represents water:

There’s water below the mountain, painting a picture of a stream welling up from the rock strata. In the story told by the Image, the mountain ‘nourishes character’ and the stream acts (or ‘goes, travels’), as it begins to carve its course and create its own nature as it flows.

‘Below the mountain, spring water comes forth. Not Knowing.

A noble one nourishes character with the fruits of action.’

The clear, new stream represents the young ignoramus’ spirit of experiment and enquiry, finding his way through trial and error.

So what might a ditch represent?

The remainder of the character du, its ‘phonetic’ element, means ‘sell’, which in turn is made up from elements meaning ‘buy’ (probably a cowrie shell in a net) and ‘go out’. In theory, this is a purely phonetic element. However… mightn’t the meanings of covetousness, avidity and over-familiarity be connected with buying and selling? Digging a ditch turns the natural flow of water into something transactional: we’ll have less water here, more over there, to match our needs.

All this casts light on the choice of du to explain ‘not speaking’. We might imagine a clear and innocent question meeting with a speaking answer as a fresh stream, and disrespectful, repeated casting as an attempt to channel the stream, leaving you with nothing more than a ditch.