A Change Circle member asked for examples and impressions of Hexagram 56, Travelling, as relating hexagram. After I’d trawled through my journal for examples for her, I thought I’d like to keep digging, so here’s the result…

I’d expect the relating hexagram to describe subjective more than objective reality, and that was what emerged from my journal: an underlying experience of being a ‘stranger in a strange land’, or at all events not comfortably at home.

It came up in readings about having to move house, unsurprisingly enough, but then also in one about the disruption of lockdown. Of course I wasn’t going anywhere, then, but the disruption of my usual routine, and especially to my usual ways of feeling connected, created the 56-ish experience.

And then there’s the one where I was asking for my role or responsibility in a situation – when the situation is actually perpetually changing, so there was no settled role where I might ‘make myself at home’ and know what I was meant to be doing.

There are two aspects to the traveller’s experience, and both of them seemed relevant to my readings. One is this sense of the scenery shifting and becoming unfamiliar, as if you’d just stepped onto a travelator. And the other is the heightened importance of what you carry with you.

‘Travelling, creating small success.

Travelling, constancy brings good fortune.’

There’s only small success to be had, because your connection with the outer world is limited; the constancy, I think, is to what you carry inside.

Line by line…

There are 63 different ways for Hexagram 56 to be a relating hexagram, of course, but let’s just look at the six simplest of these – the single lines that change to 56.

30.1

‘Treading in confusion.

Honour it,

Not a mistake.’

This line’s connection with Travelling is not hard to see: Clarity’s Travelling involves treading – walking, step by step. The confusion here at the very beginning of Clarity reminds me of the befuzzlement at the moment of waking up, and maybe especially waking up in a new place. Proust at the beginning of A la recherche du temps perdu describes something like this – how, before he was fully awake, his body’s own memory

‘offered it a whole series of rooms in which it had at one time or another slept, while the unseen walls, shifting and adapting themselves to the shape of each successive room that it remembered, whirled round it in the dark.’

Swann’s Way – Proust – translated by Moncrieff

It has that ‘travelator’ feeling of the ground moving underfoot: nothing is quite where you expected it to be.

50.2

‘The vessel contains something real.

My companions are afflicted,

Cannot come near me.

Good fortune.’

Here, I think the emphasis shifts to what you carry with you. The local people don’t follow the same standard as the traveller and won’t understand his journey; the afflicted companions can’t get close to the real substance inside the vessel.

The lack of relationship (especially here at line 2, when you might naturally reach out to connect) could be frustrating – or worrying: what if there’s something wrong with what you carry? Yet the line is reassuring: what the vessel contains is real, and their inability to approach is good fortune.

35.3

‘All have confidence. Regrets vanish.’

Why such an unusually positive third line?

Hexagram 35 is setting out to breed its gift of horses, make the most of its opportunities and generate progress – and now it can do this with a Traveller’s free-ranging spirit, unconfined by local expectations and unattached to precedent. You can see the subtle trace of Hexagram 56 in ‘regrets vanish‘: you move on, so whatever went wrong before is vanishing in the rear-view mirror.

The blend of sunlit opportunity with the freedom to move creates ‘confidence’ – also translatable as consent, trust, or consensus. There’s a clear shared reality. It’s almost the opposite idea from 50.2, where the traveller’s confidence wasn’t transferable.

(Also very different from the fan yao, 56.3 changing to 35, where the traveller tries, 35-ishly, to make the most of everything, and stokes the fire in his modest lodging rather too enthusiastically. Here’s an article on 35 as relating hexagram.)

In readings, this line is often about self-confidence: with your whole self in accord, preparing to step out into the world. But ‘all’ literally means a crowd, and it can also mean carrying people with you. (In The I Ching Made Easy, the Sorrells give as an example for this line Reagan’s 1980 election landslide.)

52.4

‘Stilling your self,

No mistake.’

Fourth lines are often asking, ‘What can I do here?’; this one’s told it can just be where it is, stop jumping about doing stuff, and this – no matter how fidgety you may feel – is not a mistake.

And that’s an unexpected message for the line where Stilling meets the Traveller – why not something more mobile?

I think this is once again to do with the traveller’s poise and self-possession, the same quality that emerged in 50.2 and 35.3. The traveller is fundamentally unmoved by his surroundings: he does not allow himself to be changed.

To set this in context, remember 52 is a response to 51, Shock and its infectious wave of panic: Stilling means stilling those reactions. The traveller has a particular way of not reacting. (This reminds me of an English woman I was talking to recently, who’d moved to Spain – with absolutely no idea of becoming Spanish or even learning to speak the language.)

33.5

‘Praiseworthy retreat.

Constancy, good fortune.’

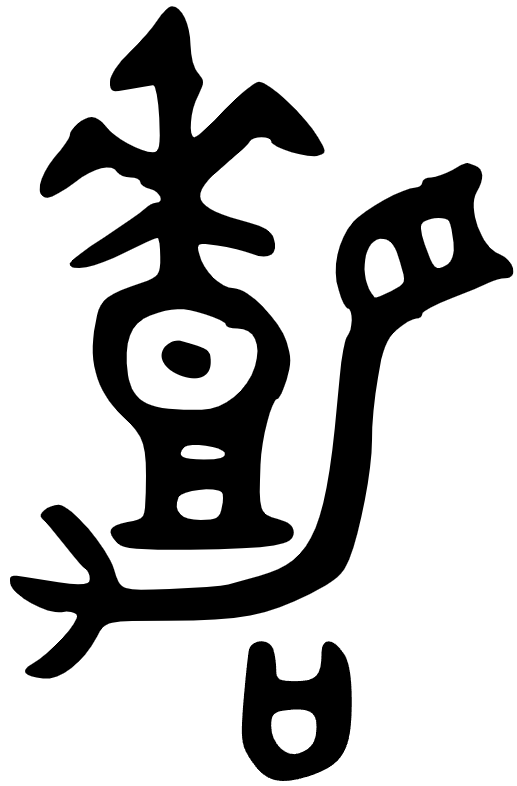

Retreating like a Traveller means a retreat that is honoured, celebrated – the drum in the ancient form of the character suggests this is something worth making a noise about.

In readings, though, actual praise may not be forthcoming: like 35.3, it’s often a matter of being inwardly sure. This line is often speaking to someone who needs to retreat from a relationship when it would be easier to stay – a matter of self-respect, and knowing oneself as an independent individual, not just a function of relationships.

You can see the connection to Hexagram 56: the traveller, on her own journey, constant to her destination and her own identity, not attached to the places she passes through. Travellers are good at retreating.

62.6

‘Not meeting at all, going past it.

Flying bird leaves.

Pitfall,

Rightly called calamity and blunder.’

In Hexagram 62, it’s vitally important to meet, to get the message: hear the flying bird’s call, come down to ground level and connect. Remember line 2 –

‘Going past your ancestral father, meeting your ancestral mother.

Not reaching your ruler, meeting his minister.

No mistake.’

where you can meet the ancestral mother or the minister; seniority doesn’t matter provided you have a working connection. And line 4 –

‘No mistake.

Not going past, meeting it.

Going on is dangerous, must be on guard.

Do not use ever-flowing constancy.’

where once again mistake is avoided when you meet the threat instead of going past it. And then in line 5, the prince makes a particularly firm connection with the one living in a cave.

Disaster in Small Exceeding comes from not meeting – not encountering face to face, not making the connection. (Hence the disastrous pantomime moment of line 3, when the attack comes from behind.)

Naturally, the Traveller is no good at this at all. He’s self-contained and detached from his surroundings; he always goes past without truly meeting. A useful quality in Retreating or Stilling, but not now. So this flying bird leaving can be said to be calamity (a disaster, like a house fire) and blunder, which is a mistake of clouded vision (the word also means cataract or eye disease). This is the traveller’s cluelessness about his surroundings coming back to bite him.