If you think about it, some stories play a big part in our conversation even though we never tell them in full. With a story everyone knows, you don’t need to tell it, you only need to allude to it. So ‘No, he isn’t Prince Charming’ becomes a short way of saying, ‘This is not the story of Cinderella: he isn’t going to single you out, lift you out of your humdrum existence into a palace of happily-ever-afters…’ and so on. We do something similar if we talk about Londoners reacting stolidly to terrorism with ‘the Blitz spirit’, or if we call a source of temptation a ‘serpent’.

Alluding to our shared stories is a tremendously succinct way to invoke a lot of meaning in just a word or two. Naturally the Yi – possibly the most succinct book in the world – uses this.

Only this makes for tricky moments in interpretation, because story-sharing is a tenuous thing. Even in the examples I just gave, the ‘serpent’ won’t mean so much to you if you’re not from a Judaeo-Christian culture, and my idea of ‘Blitz spirit’ is already a lot hazier than my father’s might have been, because he was there to help clear the rubble. (He never mentioned any ‘spirit’, but I’ve inherited his fear of the sound of air-raid sirens.) In fact… if you’re younger than I am, or American, the Blitz probably isn’t a ‘shared story’ at all.

So if I can’t even be sure what stories I might share with readers of this post, what are my chances of knowing what stories might have been shared by the first users of the oracle? And in readings, when do I get to say, ‘Here Yi is clearly referring to this story,’ when is it better to stick with, ‘This would probably have reminded a contemporary reader of this story,’ and when am I just making stuff up?

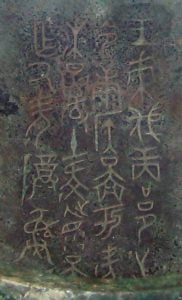

Scholars look at historical records and other ancient texts and find possible allusions. For instance, we can be fairly sure that the prince receiving horses in Hexagram 35 is Prince Kang, because of the inscription on this vessel. SJ Marshall read the history of the Zhou conquest and identified the name of Hexagram 55 with the garrison capital Feng; Stephen Field, because he’s also translated Tian Wen (‘Questions of Heaven’, a poem made up entirely of questions about Chinese myth and cosmology) is especially well-placed to recognise its characters and stories in the Zhouyi. (In fact his book is a superb source – the best I know – for both historical and mythical allusions, and gives far more detail than other sources.)

Scholars look at historical records and other ancient texts and find possible allusions. For instance, we can be fairly sure that the prince receiving horses in Hexagram 35 is Prince Kang, because of the inscription on this vessel. SJ Marshall read the history of the Zhou conquest and identified the name of Hexagram 55 with the garrison capital Feng; Stephen Field, because he’s also translated Tian Wen (‘Questions of Heaven’, a poem made up entirely of questions about Chinese myth and cosmology) is especially well-placed to recognise its characters and stories in the Zhouyi. (In fact his book is a superb source – the best I know – for both historical and mythical allusions, and gives far more detail than other sources.)

So the diviner sits on the back of the scholars, like the wren riding the eagle, and finds she can give people new stories to think in – an essential part of divination. On the face of it, the question for a diviner seems to be less ‘can I know this is a real reference?’ and more ‘will this help?’ But I’m still careful only to tell the stories I’m sure of, and ignore associations that seem to be simply the translator’s invention. Stories are powerful things – and people base their understanding and decisions on what the oracle says – and the only thing I can be sure will help, frequently in ways I can’t imagine, is what the oracle says. Diviner beware.

Here are some stories I would definitely tell as part of a reading:

The Zhou Conquest, of course, the book’s one big unifying story: the modest little Zhou people receiving the Mandate of Heaven to overthrow the Shang rulers. This is recent history for the book’s first users, rewriting their whole world, and it colours the ancient text vividly: crossing rivers, the struggle in the northeast, western neighbours, strange alliances, the long historical resonances of the marriage of King Yi’s daughters (no wonder 11.5 changes to 5!), and of course the big moments: 49, 55.

Linked with this story, there’s Prince Ji in 36 and his mirror image, Prince Kang, in 35. Then Wu in 55 also has his reflection from a much earlier time: the Shang progenitor King Hai in Hexagram 56 (and 34, and maybe also 23).

And reaching further back into mythical times, there’s Yu the Great, conqueror of floods and banisher of demons, limping on through 8, 39, 43 and 44.

I think those are the stories I would rely on, though there are plenty of other tantalising hints, and there must surely be much more that we’ve lost. Perhaps a contemporary reader would have known who was attacked by bandits in 5, or who shot the hawk in 40.6…

I think those are the stories I would rely on, though there are plenty of other tantalising hints, and there must surely be much more that we’ve lost. Perhaps a contemporary reader would have known who was attacked by bandits in 5, or who shot the hawk in 40.6…

|

Yijing, Book of Stories– an anthology. |

You are so right about the “stories, or myths” that are common to one culture but not so much to the other. Some of the stories in the I Ching are so hard to contemplate for this very reason. So we are forced to listen to the experts explain this to us, and sometimes even that is not satisfactory. That is why I like to look at everything, and every reading from as many angles as I can. Hopefully eventually I can get the right feel for a particular situation.

Just as Americans may not know about the ‘blitz,” at least not personally, I suspect some cultures may not understand if I said, “I have a bridge I’ll see you.” In modern times we are more likely to say, “I have some ocean front property in Arizona I will sell you.” The bridge is a reference to the Brooklyn Bridge which in times past, con men might try to sell, although it is obviously not for sale, and not privately owned. Each culture, I am sure has its own way of saying things, and referring to stories that are specific to that culture. But with time things change, and our stories change, and the past is eventually forgotten by all but a few. It does result in problems.

Oops, I meant sell, not see, for the bridge.

Hm – I’d know what was meant by ‘sell you a bridge’ (there’s a nice one in London that opens; bids invited from wealthy American tourists…) but I hadn’t heard about the ocean property in Arizona.

What helps me get inside the Yi’s stories is telling them – again and again, to different people in different circumstances. Then they come to life.

Thank you so much for this, but especially for the historical frame for 49 Revolution -> 55 Abundance. It so enriches the celebratory tone of “The great one” charging like a tiger in 49.5, the transition line to 55.

Stephen Field is now on my reading list!

Yes – that’s a remarkable line change, bridging a remarkable arc of hexagrams. And its fan yao, 55.5 –

– can suggest the new Zhou order and the cosmic harmony that goes with it.