For some 3,000 years, people have turned to the I Ching, the Book of Changes, to help them uncover the meaning of their experience, to bring their actions into harmony with their underlying purpose, and above all to build a foundation of confident awareness for their choices.

Down the millennia, as the I Ching tradition has grown richer and deeper, the things we consult about may have changed a little, but the moment of consultation is much the same. These are the times when you’re turning in circles, hemmed in and frustrated by all the things you can’t see or don’t understand. You can think it over (and over, and over); you can ‘journal’ it; you can gather opinions.

But how can you have confidence in choosing a way to go, if you can’t quite be sure of seeing where you are?

Only understand where you are now, and you rediscover your power to make changes. This is the heart of I Ching divination. Once you can truly see into the present moment, all its possibilities open out before you – and you are free to create your future.

What is the I Ching?

The I Ching (or Yijing) is an oracle book: it speaks to you. You can call on its help with any question you have: issues with relationships of all kinds, ways to attain your personal goals, the outcomes of different choices for a key decision. It grounds you in present reality, encourages you to grow, and nurtures your self-knowledge. When things aren’t working, it opens up a space for you to get ‘off the ride’, out of the rut, and choose your own direction. And above all, it’s a wide-open, free-flowing channel for truth.

Hello, and thank you for visiting!

I’m Hilary – I work as an I Ching diviner and teacher, and I’m the author of I Ching: Walking your path, creating your future.

I hope you enjoy the site and find what you’re looking for here – do contact me with any comments or questions.

Clarity is my one-woman business providing I Ching courses, readings and community. (You can read more about me, and what I do, here.) It lets me spend my time doing the work I love, using my gifts to help you.

(Thank you.)

Warm wishes,

Hilary”

Blog

Outside the boxes

When I first heard about Benebell Wen's I Ching, I thought it sounded unpromising. An I Ching book by someone who had already published on tarot, who maintains a website with sections on feng shui, numerology, Western astrology and esoteric Taoism as well as tarot and the I Ching, all while working full time as a corporate lawyer. This was going to be one of those sad little pamphlet-sized offerings of undigested, rehashed Wilhelm/Baynes, right?

(pause)

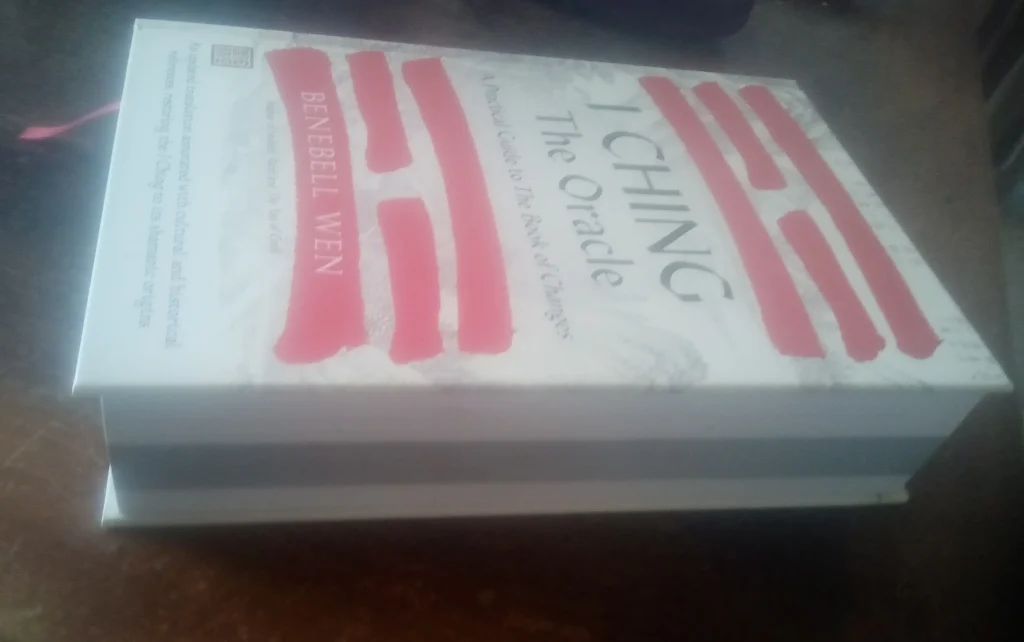

Er, no. (That's 900+ pages.)

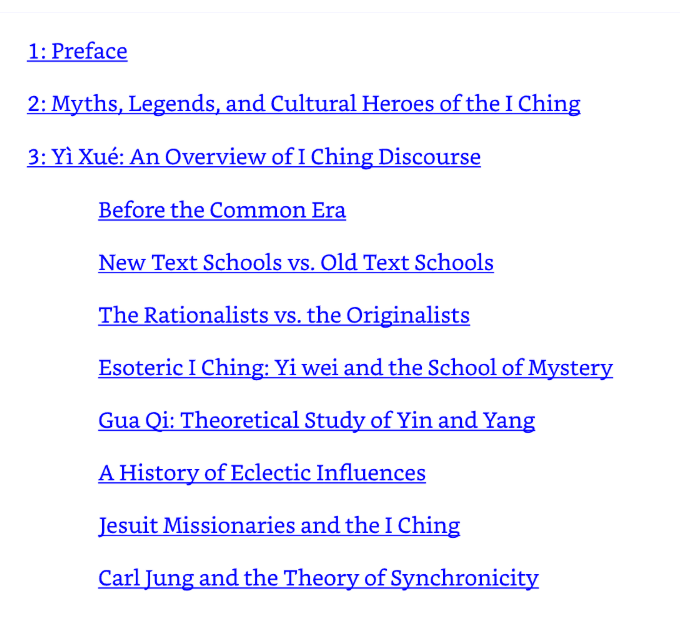

Also, take a look at the table of contents, included in Amazon's excerpt from the Kindle version. Here's how it begins:

...and it continues; do have a look. (The Kindle version is ridiculously cheap in the UK at the moment, by the way.)

So this really does not fit into the box I had ready for it, or indeed any box I can think of. That chapter on Yixue suggests why: Benebell Wen is very well aware of how many different ways there have been of engaging with and understanding the Yi over the millennia. She's not a disciple of any of them, and sees no reason not to draw on them all, or find new ones.

I'd recommend reading what she has to say about the book on her own website, where she calls it both an 'I Ching reference book' and a 'magical grimoire'. She also shares some generous excerpts to give you a flavour of it, including its unique 'practicums'.

Why buy it?

Again - just look at the contents list. That Yixue chapter ranges across Yi's history through China, East Asia and Europe, up to the present day. She's especially good at bringing her knowledge to life. There are many vivid stories from myth and legend, all great imagination food for readings. I'd never before read about Yu the Great receiving jade tablets of magical secrets from Fuxi in a cave, for instance. (It's odd she doesn't mention this one when she gets to 62.5!)

I especially appreciate her portraits of the trigrams, with associated immortals and Feng Shui/ magical/ meditative practices. That whole practical, 'practicum' element of the book, the 'grimoire', is something I've not seen elsewhere, certainly not with these strong Taoist roots.

The introduction doesn't attempt to separate out tradition from history - it tells both in a single story - and so we end up with yin and yang appearing at the beginning, and the Early Heaven bagua before Later Heaven. (Her videos on Youtube have the occasional error, too, though they're still well worth watching.) But better vivid, living tradition with some inaccuracies than dry-as-dust academic correctness, perhaps?

That rich imagination-food continues throughout the translation, which is interspersed with panels telling all kinds of stories from myth and history. And these are Benebell's own versions of the stories: 55's (possible) eclipse comes with a magus who fails to reverse it and has his arm broken in punishment at line 3. Wang Hai shows up in hexagrams 23 and 56, but he's innocent of all wrong-doing, except perhaps in a remote footnote. She's not just following in the footsteps of academics, and there will definitely be associations here you haven't seen elsewhere. Hexagram 54, for instance, will tell you about Tai Si, but also Chang-Er, who went to the moon. 44.5 comes with a page about 'Jiang Ziya, the white muskmelon'.

She presents all these as associations and possibilities, never as the One True Meaning. I imagine she's much too aware of the different meanings lines have held for different people over the centuries to fall into that trap. So her account of Hexagram 55 ends with a panel on eclipses, with their dates, but notes that whether the text refers to either 'is a matter for speculation'. Which is good, because 'here is what this hexagram is about' is just not how readings work.

Translation troubles

(Sadly, there are some.)

No Oracle/ Image

Benebell does not translate the Oracle/Judgement and Image in their entirety. Instead, you get bits of each, interspersed with her commentary, and all blended together. Most Yijing translations use different typefaces to differentiate between translation and commentary - and she does the same with the moving line texts, but not with Oracle and Image. Here, the bold text is a mish-mash of translation and commentary.

Here's Hexagram 28, as an example. She translates the whole as 'Undertake the Great', not 'excess' or 'transition' or 'crossing the line'. (She's not at all consistent in her translation of guo - you wouldn't know that 62 is the small version of the same action.) After a summary of how she interprets the hexagram as a whole, comes -

The lake rises over the trees; marsh submerging wood. Embarking on a great endeavor. The sage is independent and fearless, ever concerned for the world. Let the heart be stable and calm, no matter what conditions endeavor to challenge it. A fragile, unstable roof beam - a critical situation.

Renouncing the world you knew. Expelling melancholy. It is a tipping point. You are reaching critical mass.

Yet fortune favors the inquirer - 利有攸往 (li you you wang). Undertaking a great challenge is likely to yield success, so proceed with confidence.

Take the transformative path. It is a turning point in your life.

There's no way you could reconstruct the original text from this - which is a shame, because the original has its own internal logic:

'Great Exceeding, the ridgepole warps.

Fruitful to have a direction to go.

Creating success.'

That sounds to me as though it's useful to have somewhere to go because of the state of the ridgepole. And likewise with the Image: the original has a prevailing theme of being alone, withdrawing, which is diluted or demoted in her version.

Oddnesses and inconsistencies

The translation of the lines is full of interesting ideas, and some quite odd ones, but none of them seems to be consistently applied through the book. Again and again, I come across an intriguing translation that makes me sit up and take notice, look to see what she's made of the same word or words elsewhere, and find there is no similarity at all: it's as if the lines had been translated by different people.

For instance…

The final three words of 18.1 are 厲終吉 li zhong ji, which I translated, quite conventionally, as, 'danger, in the end good fortune.' Benebell has something very different:

'The whetstone comes to the end of its life - auspicious for the future to come; prosperity and great fortune.'

And she picks up on this in her commentary on the line:

'The whetstone, or a stone used to sharpen metal tools, axes and daggers, symbolizes refinement and the strengthening of character through friction; it's also a symbol of cultivating a new warrior king.'

Li, usually translated as an omen word meaning 'danger', did also mean 'whetstone', and there is no punctuation in the original, so 'danger; in the end, good fortune' might also mean 'whetstone ending; good fortune.' Certainly the symbolism of the whetstone as she describes it feels like good, rich stuff for readings.

Exactly the same phrase - 厲終吉 li zhong ji - occurs in Hexagram 6 line 3, where she translates:

'…leads first into trouble, but then to prosperity.'

There's not a ghost of a whetstone here, nor for any other instances of li that I've come across so far in the book.

There are lots of examples like this: she'll pick a character, draw out its ancient etymological associations, make them central to a translation or interpretation - and then completely lose sight of them for every other instance of the character.

One more example - 5's crows.

The first bolded sentence for Hexagram 5 is 'Crows above the clouds.' There's a whole page about 'The crow and the totemic emblem of the Shang because '於 Yu is a reference to a bird in the sky.'

Wait… crows? What's this yu character where she found them?

It's the one used in all the lines of Hexagram 5 as a preposition after 'waiting' (and then after 'entering' in line 6): waiting at the outskirts, on the sands, and so on. Obviously it couldn't be translated here as 'crow', and she doesn't attempt that - but she does make the crow a core part of the hexagram's meaning.

If I'm reading the dictionary correctly, 於 could mean 'crow' when pronounced differently; she hasn't invented this. But the word is used liberally throughout the Zhouyi as a preposition, including in every line of Hexagram 53 in exactly the same way as in the lines of Hexagram 5. (The wild geese gradually progress yu the shore, the rocks, and so on.) I didn't manage to count all the occurrences of yu in the book, but there are more than sixty. Not so much as a feather of a crow accompanies any of them in translation or commentary.

I'm left feeling as though this is partly a translation, partly a riff on individual character associations - not connected with the character's meaning in the sentence, and not part of any decision for the translation or interpretation as a whole.

I don't know why she's done this, but I'm going to hazard a guess that perhaps this has to do with her experiences as a diviner. (She does use the Yi for readings.) I think singling out a character's associations in a reading can work: there could be a single moment of synchronicity when it's revelatory for Hexagram 5 to remind you of crows.

So… perhaps these associations come from such one-off reading experiences? I'm just not persuaded that they belong in a book people will consult for every reading. There, I want imagination food, yes, but with consistency, thought through with care. Partly so it won't send you on wild crow chases unrelated to your reading, and also partly so you can trace real associations from one reading to the next.

(If you cast 44.5 about a topic and later cast 55.5 about something connected, ideally your translation should let you see how Yi is referring back to the previous reading and telling you your story. Benebell has fascinating insight into 44.5 which disappears completely from 2.3 or 55.5.)

Who's this for?

Sadly, not for beginners, because of its translation troubles. If you're going to be introduced to the I Ching, you need to start with the I Ching in as direct a translation as possible. (I know it isn't altogether possible.) Without that, you can never truly connect with the oracle.

It's a shame, as that generous, eclectic introduction would be a lovely place to start, just to get a sense of the scale of the book and the diversity of approaches available.

But if you're no longer a beginner, if you have access to a translation or two and would like to explore further and have your ideas about Yi, its meanings and uses and roots, expanded, then definitely buy this one. You'll love it.

If you look at that 'this is not a pamphlet' photo, the pages identified with the grey margins are the translation, and all the rest is background: history, myth, stories, esotericism from Crowley to Taoist magic, trigrams and DNA and Boddhisattvas… the whole technicolor panoply of the I Ching across time and space. (Or at least more of it than I've ever seen in one place before.) All this, and a fat bibliography and footnotes.

She uses a great breadth of sources, something that really comes across in the footnotes. Note 47 to the translation refers to an obscure academic paper about an incident in the life of King Wen. Note 48 proposes ritual magic remedies 'for amplifying Wood and Thunder to counteract the blockading effects of Hexagram 47.' Note 49 refers to something from Yale University Press. A later footnote tells you in detail how to use 56.1 as a curse. Like I said, I haven't found a box this book will fit in.

I also appreciate the way she uses all this: the eclipses of 55 being 'a matter for speculation'; how she suggests a Taoist mystic could 'repurpose' 64.4 (where the Thunderer subdues the Demon Country) as spell-crafting instructions. She has lots of ideas, she makes them available, and doesn't try to nail anything down or claim that she know 'What It Means'.

I won't be relying on anything here as a sole source of information, but I also wouldn't want to miss out on the breadth, depth and richness of it all. Do visit her site and explore.

Following on from a previous post…

Hexagram 20, Seeing

Hexagram 20 has xun, wind and wood, over earth; its Oracle text suggests earth's open, available quality:

'Seeing. Washing hands, and not making the offering.

There is truth and confidence like a presence.’

Earth will not act, but allows: the ritual provides space for truth to arise, like the earth provides space for seeds to germinate. If you're from a Christian culture, these trigrams might remind you of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit (spiritus - breath, wind) came first as a strong wind.

The Image as ever, gives a quietly practical perspective:

‘Wind moves over the earth. Seeing.

The ancient kings studied the regions,

Saw the people,

And established their teachings.’

The ancient kings studied and saw, with earth-like qualities, and established teachings that would carry culture as far as the wind.

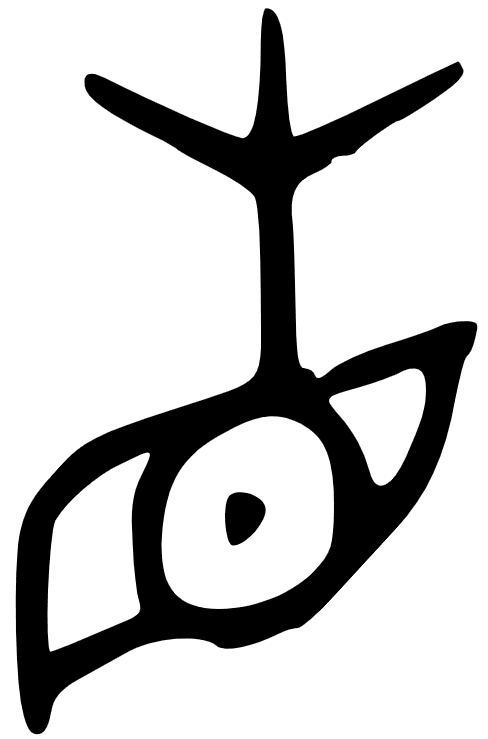

The character she 設, 'established', is formed of a mouth speaking and hand acting, and naturally speech belongs with xun, wind. 'Studied' is sheng 省, meaning to inspect, examine or watch over, including in a ritual inspection of mores. The character originally shows an eye with a sprouting plant appearing to grow from it:

The Pleco dictionary suggests an original meaning for sheng of a crop inspection, something very relatable for me at the moment (are those aphids on that pepper plant?). But it seems the character was always drawn with the plant growing from the eye, as if from the earth, and wait, don't we know some trigrams about that?

The teachings grow from Seeing like the plant grows from the earth. Outer xun, with its open yin line at the base, joins with earth, is open to it, and emerges from it. The kings, embodying the two trigrams, both respond to conditions and ultimately create them.

Hexagram 23, Stripping Away

With mountain above earth, we're only a single line away from Hexagram 2. But whereas in its Oracle, 'the noble one has somewhere to go,' in a time of Stripping Away, it's 'fruitless to have somewhere to go.' When things are ending, falling away - or being taken away - there's little point in thinking of where else you’d like to get to. Stand on the plain, look up and see the mountain in your way: you are here.

(When 23.6 changes and the mountain becomes earth, 'the noble one gets a cart' and he's back on the road.)

You can imagine - and I think the Image authors did imagine - the mountain eroding into the earth below. Although we analyse hexagrams into two groups of three lines, they don't all look like that at first glance:

Hexagram 23 looks like a group of five contiguous broken lines, with a single solid line above: the mountain's yin lines look like an extension - or a deepening - of inner earth. And sure enough…

'Mountain rests on the earth. Stripping Away.

The heights are generous, and there are tranquil homes below.'

…there is generosity above, just as 'generous de' is a quality of earth -

'Power of the land: Earth.

A noble one, with generous de, carries all the beings.'

It's the same word in the Chinese, 厚 hou, meaning deep and thick as well as generous, and it occurs only in these two hexagrams, the ones with the deepest soil.

The 'tranquil homes' are another echo of Hexagram 2, this time from its Oracle, which ends - after all its travels - with 'tranquil constancy, good fortune.' An 安, tranquil, is one of my favourite Chinese characters:

It shows a woman at home, under her roof - and its shape reminds me irresistibly of 23's component trigrams, with outer mountain in its role as protector, securing the space - not against loss, but through it.

Hexagram 35, Advancing

'Advancing, Prince Kang used a gift of horses to breed a multitude.

In the course of a day, he mated them three times.'

The 'course of a day' is found in Advancing's component trigrams: the sun over the earth. Bradford Hatcher saw this as the earth energised by the sun, and given order:

'More than light is dawning here. This energy coming into the system not only powers the system: it will organize it too, in the same way that good health will clarify the mind.'

So if the sunlight is powering and organising, what's the role of earth? It provides the sun with something to shine on - something that can respond and be brought to life.

That responsiveness is Prince Kang's: he is ready to commit his energy to breeding the horses, multiplying his gifts. And, of course, it's found in the fertility of the mares, who are the multiplier in all this! (This is horses' second appearance in an Oracle text.) It seems to me to be the same earth-readiness, supporting the outer trigram so its potential can be realised, that you find in hexagrams 8 and 16 (and 45).

Then the Image…

'Light comes forth over the earth. Advancing

The noble one's own light shines in her de.'

…makes clear something we might have missed from the Oracle: that this is not just about the happy chance of a blessing falling from above.

The lucky break has to be part of its meaning: Kang's counterpart in Hexagram 36, Prince Ji, was surely just as willing and virtuous as he was, but could do nothing but hide his light. But the hexagram is not just about being lucky. The light comes forth from the earth, with the same verb that was applied to the thunder of Hexagram 16: chu 出, to come out from, emerge from. This is the noble one's own light: it comes from inside, sustained by their own energy.

Hexagram 45, Gathering

'Gathering, creating success.

With the king's presence, there is a temple.

Fruitful to see great people, creating success.

Constancy bears fruit.

Using great sacrificial animals: good fortune.

Fruitful to have a direction to go.'

This might be the fullest expression of earth's willingness to support. Prince Kang lent his energy to horse-breeding; in Hexagram 45, the king, the great people and an offering of the biggest and best animals all support the Gathering. We can picture all the people congregating at the temple with shared purpose.

The trigram picture here is lake above the earth - a reservoir contained by high earth banks. The Image sees the risk this represents:

'Lake higher than the earth. Gathering.

A noble one puts weaponry in good order

And warns against the unexpected.'

From the earliest commentaries, people have recognised that the noble one is warning against the risk of flooding. Gathering all your water in one reservoir has its advantages but also its dangers - all the more so if ordinary people live in pit dwellings.

The role of earth in this picture is clear enough: it contains the water, creates the reservoir, and protects against flooding. It quite literally 'provides the how' - the building material for the banks.

Why does the noble one prepare weapons, though? (This is assuredly what she does: the character for 'warning' or 'guarding against' is the same as in 62.4, and originally showed two hands grasping a weapon.) Wang Bi implied that she was guarding against an emergency when societal consensus might dissolve into an 'every man for himself' mindset.

I tend to think of the depth of water in the lake as a deep emotional investment that can easily run out of control. It doesn't take much for the banks to breach - that's why the police prepare for big football matches. And breaches happen in the individual psyche, too, when we give something all we have. Earth qualities here might mean an openness and readiness to respond to outcomes that aren't what we had in mind.

Charlie asked 'How to navigate?' and cast Hexagram 27, Nourishment - or Jaws - changing at line 1 to 23, Stripping Away:

What followed was a strongly resonant conversation between his inner imagery and the imagery of the Yi - and also the ancient Chinese motif of being in the jaws of the tiger. The featured image above this post shows a detail from the handle of the Houmuwu vessel, where you can just see the human face between the tigers' open mouths. (The original photo is by Mlogic, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Here's another example, from the 11th century BC:

Earth inside

The easiest way to get to grips with the first two hexagrams, for me, is always to think how much they're not each other. Qian, the creative force of heaven: nothing but solid lines, like the paths of sun, moon and stars across the sky. It moves without ceasing, and we can't change it - not by a millimeter or a millisecond. Kun, earth: nothing but open lines, like the soft earth ready to be shaped by roots, or water, or footprints, or hands, or the plough, to take the shape it's given and provide whatever is needed to bring the creative impulse to full expression.

So when I start looking at how kun works as an inner trigram, I notice first how it isn't inner qian. As an inner trigram, heaven might feel like your irreducible will, life force and creative drive: that part of you which will not be changed, or made to swerve or turn aside. So kun inside could be sustaining and realising power, something that provides the 'how' for the outer trigram; it can also be the power of responsiveness, even malleability.

Let's see…

Hexagram 2, Earth

Earth inside, earth outside: a whole broad expanse of open land waiting for footprints, like the way stretching out ahead of the noble one with 'somewhere to go' of the Oracle text, or the field for the mare:

'The mare is the earth's kindred spirit,

And wanders an earth with no borders.'

(Bradford Hatcher's translation of the Tuanzhuan)

I think the Image authors saw Hexagram 2 as soil:

'Power of the land: Earth.

A noble one, with generous de, carries all the beings.'

To quote myself…

I wonder whether the Image authors might not have been looking down instead of out and across, and thinking of the depth of soil beneath their feet:

‘Power of the land: Earth.

A noble one, with generous character, carries all the beings.’地勢坤,君子以厚德載物

‘Soil power’! The word for power, shi 勢, is a lovely choice: its component parts are ‘strength’ and ‘agriculture’ – a component (purely phonetic, apparently!) that shows a person kneeling to plant a seedling. In many old versions of the character, they’re holding the plant up above head height, in a way that – to my very-amateur-gardener’s soul – seems like something between exultation and prayer. (‘Look, it’s growing! Can the pigeons please not eat it?’)

And the noble one, mirroring the power of the land, has ‘generous character’, 厚德 hou de – where hou also means thick, deep, dense, profound and weighty. The six broken lines of the hexagram start to look like really deep, rich soil – not just a dusty layer that could blow away. This deep kindness will carry all beings.

Generous de (character/ virtue/ power) is like good earth: all six broken lines, open and friable, with no rocks to dig through. And this power is ready to carry everything - literally to be loaded up like a wagon. That gives me the sense not only of earth's readiness to lend support, but also of carrying things forward, to their natural destination. Qian might bring the 'what' - or maybe more the 'why' - but kun will provide the 'how'.

Hexagram 8, Seeking Union, Belonging

Earth inside, with water running over it.

'Seeking union, good fortune.

At the origin of oracle consultation,

From the source, ever-flowing constancy.

No mistake.

Realms not at peace are coming.

For the latecomer, pitfall.'

What could be the role of earth here?

It could be the water's source: perhaps water is welling up from the earth, like the 'origin of oracle consultation' in inner openness. (Look at where we've come from in the Sequence, too.) Earth could be your willingness to be guided, and the unfortunate latecomer was just not available enough.

It can also be the banks of the river, its course shaping and shaped by the water's flow. Then earth could be what supports and lends shape to your unceasing emotional-intuitive flow of commitment in the world. ('On second thoughts, stop a minute, I'll just go back up the hill and see if there's an alternative route,' as rivers, on the whole, do not say.)

Then the Image shows earth at work:

'Above earth is the stream. Seeking Union.

The ancient kings founded countless cities for relationships with all the feudal lords.'

Earth provides the 'how': without the cities, there could be no relationships. I've tended to think of this one as a matter of political/military strategy, but it's really much more than that. The 'relationships' here, 親 qin, are close and personal: ancient meanings include close family, intimacy, cherishing, the love of parents, siblings and children.

So… perhaps we could imagine outer kan as the flow of love, and inner kun as everything that supports it: all the practical things you do to uphold a relationship.

Hexagram 12, Blocked

This is really the odd one out. With the other seven 'earth inside' hexagrams, I can start by asking how earth interacts with the outer trigram, how it supports it, responds to it, is shaped by it, provides the 'how' to realise it… but in Hexagram 12, 'Heaven and earth do not interact.' The Image says so, bluntly; so too does the Tuanzhuan:

'Thus heaven and earth do not unite, and all beings fail to achieve union. Upper and lower do not unite, and and in the world, states go down to ruin.'

(Wilhelm/Baynes translation)

I think it was Sarah Denning who connected this one with the quotation from Waiting for Godot:

"Nothing happens. Nobody comes, nobody goes. It's awful!"

Exactly. So what can we do with or learn from the trigrams here?

'Heaven and earth do not interact. Blocked.

A noble one uses her strength sparingly to avoid hardship.

She does not allow herself honours and payment.'

'Uses her strength sparingly' - literally, the noble one uses 'frugal de', jian de 儉德. That's a direct contrast to Hexagram 2, where she uses hou de 厚德: generous de. The two sentences have exactly the same structure:

| The noble one thus | frugal | de | avoids | hardship. |

| The noble one thus | generous | de | carries | beings. |

'Frugal' means thrifty, the opposite of profligate, and also crop failure. In these times, 'the noble one's constancy bears no fruit': nothing is growing; generous de wouldn't work. So in a sense, the noble one makes active use of the trigrams' non-interaction by withholding her own inner strength, keeping her earth-like capacity to herself.

Not allowing honours or payment seems to me to be the action of the outer trigram heaven - not connecting with earth, but continuing unswerving and uncompromised. (I like Bradford Hatcher's explanation of this as 'not taking bait, not giving wrongness something to rally and live for'. We've all had one of those arguments where you are only giving energy to the wrongness, not getting anywhere.)

Looking at the two trigrams together, you can also imagine standing quietly on the earth and not trying to capture the stars. For a clearer sense of this, contrast it with Hexagram 10, Treading: heaven above, but lake below, reflecting the depths of heaven, aspiring towards it.

Hexagram 16, Enthusiasm/ Anticipating

'Thunder bursts forth from the earth!' We should imagine springtime, when everything that has been dormant in the earth surges upwards into life.

The trigrams are already visible - or imagin-able, at least - in the Oracle text:

'Enthusiasm.

Fruitful to set up feudal lords and mobilise the armies.'

Thunder sets things in motion, so that looks like mobilisation; then the earth would correspond to the feudal lords, providing the structure that makes it possible. The earth trigram inside Hexagram 16 feels a lot like the one inside Hexagram 8: lending all possible strength and support.

In the Image, you can feel the wholehearted generosity of its commitment:

'Thunder bursts forth from the earth. Enthusiasm

The ancient kings composed music to honour de,

They celebrated and worshipped the supreme lord,

Joining with their ancestors.'

The ancient kings are honouring virtue, chong de 崇德; chong means to respect and elevate, exalt - the character is made of 'ancestral temple' and 'mountain'. So their music uplifts de like the earth supports the thunder that rises through it; it's the same idea we know from familiar psalms and hymns of voices rising to heaven.

I think they also use earth-qualities to 'join with their ancestors' - or as Wilhelm beautifully puts it, to invite them. The idea here is of matching, being worthy of, being in accord with. That suggests the responsiveness of earth, open to invite a spiritual presence, and following in the ancestors' footsteps like the noble one of Hexagram 2: 'following behind, gains a master'.

It's also important that their music has structure, transforming raw enthusiasm into harmony. In the same way, the interconnected web of feudal lords will turn the people's strength into an army, and the matrix of soil will support the new plants' growth.

(Hexagrams 20, 23, 35 and 45 to come!)

I've been working on a post on the trigram kun, earth, as inner trigram. That one will come soon - this is just something I wondered about along the way.

I started going through the sequence of hexagrams, looking at the Image texts for the ones with earth inside...

'Above earth is the stream. Seeking Union.

The ancient kings founded countless cities for relationships with all the feudal lords.''Thunder bursts forth from the earth. Enthusiasm

The ancient kings composed music to honour virtue,

They celebrated and worshipped the supreme lord,

Joining with their ancestors.'‘Wind moves over the earth. Seeing.

The ancient kings studied the regions,

Saw the people,

And established their teachings.’

I'd got about this far when I was distracted by the ancient kings: there seemed to be a great many of them about. Was this a pattern, or a coincidence?

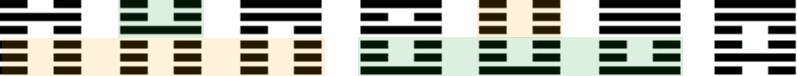

Well… there are seven hexagrams that mention the ancient kings in their Image text: 8, 16, 20, 21, 24, 25 and 59. Of these, three have kun as their inner trigram, and then there's also 24 with kun as outer trigram. If the distribution were random, I don't think you'd expect to see it more than a couple of times overall, and once as inner trigram.

So are the ancient kings especially like earth? Mothers to their people?

Perhaps. But this is only half the picture: the trigram zhen, thunder, also appears three times as inner trigram and once as outer trigram in 'their' hexagrams. The ancient kings are also innovators, the inner impulse that set civilisation in motion.

The arrangement of earth and thunder through these seven hexagrams is oddly symmetrical, look:

Here they all are, ignoring the actual distances between them in the sequence. (What is Hexagram 59 doing out there on a limb?)

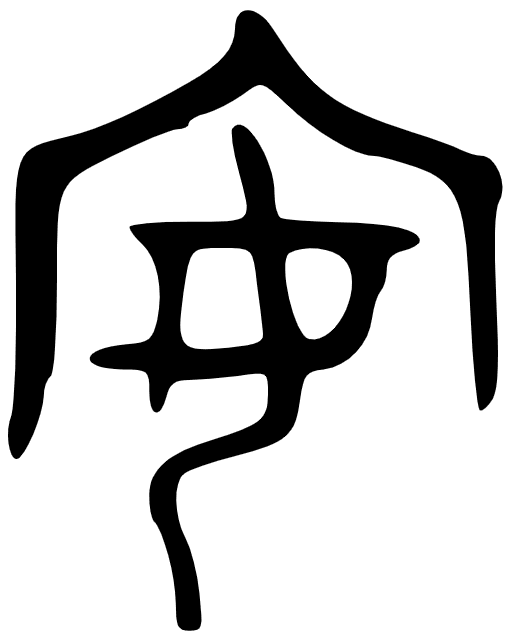

And here's the character wang, king:

王

It's been written much like this since early times: three horizontal strokes joined by a single vertical one through the centre.

(Not for the first time, I feel as though I'm catching on v-e-r-y s-l-o-w-l-y...)

How does the Yi help in an impossibly painful situation? It's hard to describe - deep recognition, being recognised, a sense of reconnection. Dominique's reading for this episode:

"What is the lesson that I must learn through the pain of losing my marriage and our future?"

And Yi's answer: Dispersing - Hexagram 59, with no changing lines.

It's a beautiful response - I hope you enjoy listening

Transcript, for Change Circle members

I Ching Community

Podcast

Join Clarity

You are warmly invited to join Clarity and –

- access the audio version of the Beginners’ Course

- participate in the I Ching Community

- subscribe to ‘Friends’ Notes’ for I Ching news